Long Gamma vs Short Gamma: Beginner's Guide

Gamma measures how much an option’s delta changes with a $1 move in the underlying. Long gamma positions, such as long calls and debit spreads, benefit from big moves but lose value to time decay. Short gamma positions, such as short options and credit spreads, profit when prices stay steady but take losses quickly if the market moves.

Understanding your gamma exposure is crucial to any options trader’s success. Not knowing gamma is like not knowing which way your sails will turn when the wind changes. It’s the Greek that shows how quickly risk can build or ease as the market moves.

Highlights

- Gamma measures how much an option’s delta changes with a $1 move in the underlying.

- Long gamma positions, like buying calls or debit spreads, benefit from sharp moves in the stock but are hurt by time decay.

- Short gamma positions, like selling calls or credit spreads, profit if prices stay steady but take losses quickly when the stock makes big moves.

- Understanding gamma exposure is essential because it shows how fast risk can accelerate as the underlying shifts.

- At the money options have the highest gamma because their deltas change the most with small moves in the stock.

What Are the Greeks?

In options trading, the option Greeks are a set of risk metrics that help estimate how an option’s price will respond to changes in key market variables. They are always in motion, shifting in response to volatility and the price of the underlying asset.

Here are the five most important Greeks to know:

- Delta – shows how much an option price changes for a $1 move in the stock.

- Gamma – shows how much delta shifts when the stock moves $1.

- Theta – shows how much an option loses value each day from time decay.

- Vega – shows how much an option price changes for a 1% change in implied volatility.

- Rho – shows how much the option price changes for a 1% change in interest rates.

Because gamma depends on delta, it is considered a secondary Greek.

.png)

What Is Gamma?

The options Greek gamma measures how much an option's delta changes with a $1 move in the underlying asset's price. For example, if an option has a gamma of 0.05, a $1 move in the underlying asset will increase or decrease the delta by 0.05. Gamma can be thought of as the ‘delta of the delta’.

It is, therefore, very difficult to understand gamma without first understanding delta. Lucky for you, I've written a comprehensive article on delta. 👇

The Range of Gamma

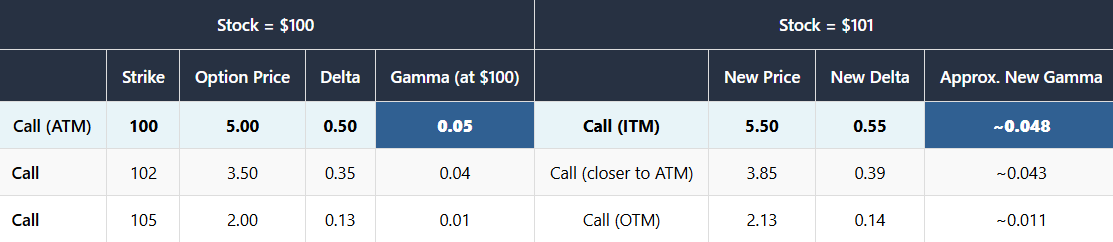

For long options, gamma ranges from 0 to +1 in theory, but in practice, values are much smaller. Gamma peaks at the money, since delta changes the most with small moves in the stock. It falls toward zero for deep in the money and far out of the money options.

For short options, gamma ranges from 0 to –1. Instead of working in your favor, delta shifts against you as the stock moves. A short call or short put carries negative gamma, which means small moves in the stock can quickly increase risk.

Gamma Example

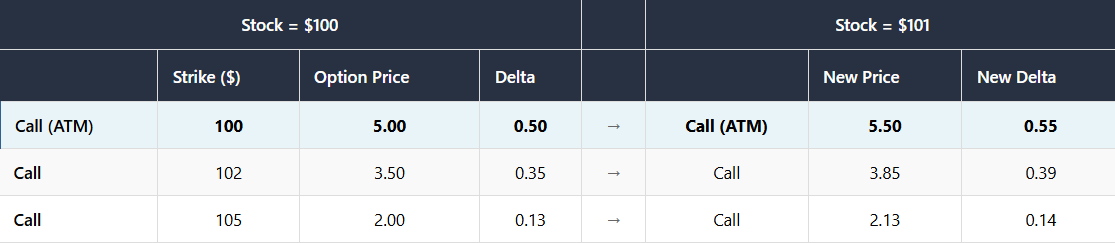

To understand how gamma and delta work together, let’s take a look at an example, focusing first on delta.

We’re going to look at a stock which currently has a price of $100/share, and show what happens to the deltas of various call options as the stock rises by $1.

For the 100 strike call, the initial delta was 0.50 when the stock traded at $100. When the stock rose to $101, the option’s value increased from 5.00 to 5.50, consistent with the original delta of 0.50. After the move, delta rose to 0.55. The difference between the old delta (0.50) and the new delta (0.55) is 0.05, which is the option’s gamma.

Because we are dealing with long calls, this gamma is positive. If we had sold these calls instead, gamma would be negative, and the change in delta would have worked against us.

We can now update the table to include the original gamma, as well as the forward-looking delta and an approximate new gamma after the $1 move.

This updated table shows how gamma shifts as the stock moves. At $100, the 100 call had the highest gamma with a delta of 0.50, but once the stock rose to $101 its gamma slipped because it was no longer at the money. The 102 and 105 calls, which were further out of the money before, are now closer to the money and their gammas increased.

Gamma and Moneyness

Let’s go more in-depth on moneyness because this is important.

On our previous tables the at the money option had the highest gamma. That is true for all options; gamma peaks with at the money options, and begins to shed the further in our out of the money the option is:

- Far out of the money options have very low gamma because delta is already near zero and barely moves when the stock price changes.

- Deep in the money options also have very low gamma since delta is already close to one and won’t shift much further.

- At the money options carry the highest gamma because they’re the most sensitive to stock price movement.

For example, let’s say you are long a 100 strike price call option on ABC the day before option expiration. If ABC is trading at $100/share, what are the odds your option will finish in the money? About 50/50.

However, if you are long a 105 call option on ABC, there is (assuming low volatility) an almost zero percent chance that it will close in the money. Gamma is low here because the option’s delta is unlikely to change significantly. Even if the stock rallies $1, the option will remain relatively worthless because a $1 move in the underlying does little to help a 105 strike price. Since gamma is derivative of delta, they will both be close to zero.

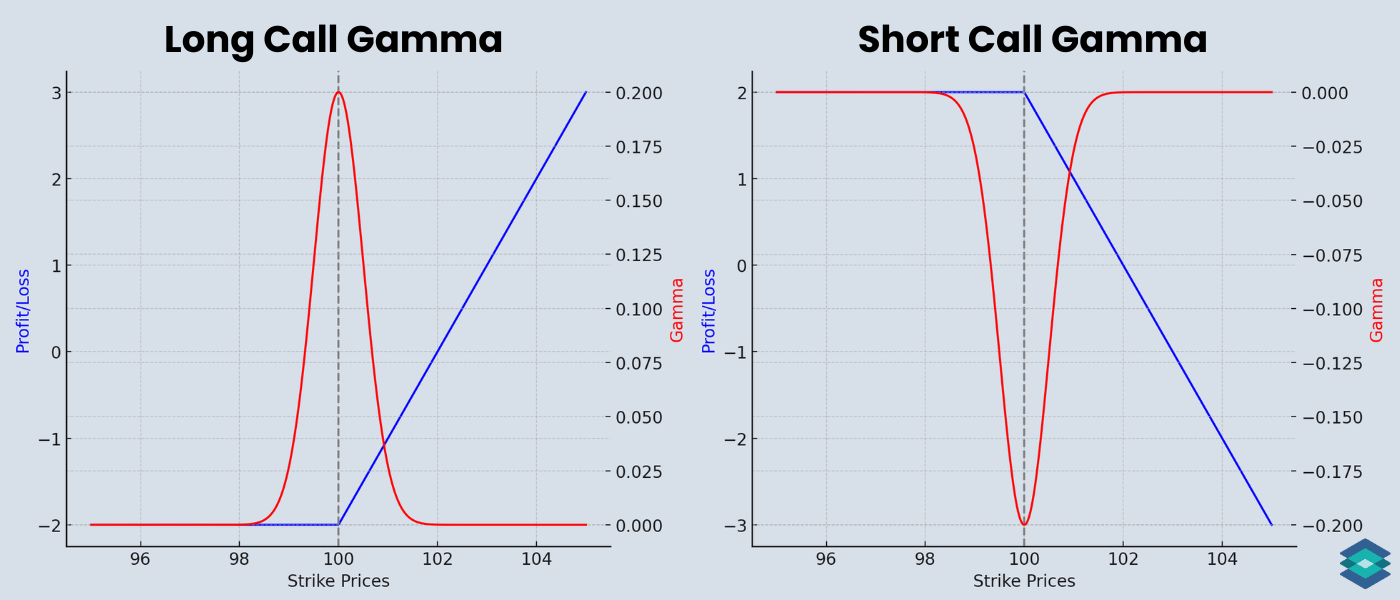

Gamma and Time Decay

Gamma and time decay often work against each other. Options with high gamma are usually close to expiration, which also means they lose value quickly from theta. In other words, the more horsepower you have from gamma, the faster the fuel burns through time decay.

- Long gamma: Gains from big moves but suffers fast theta decay.

- Short gamma: Loses on big moves but benefits from steady theta decay.

Long vs Short Gamma

Net long option positions (calls or puts) are long gamma. That means deltas move in your favor: they increase when the stock rises and decrease when the stock falls.

Short option positions are short gamma. That means deltas move against you: they fall when the stock rises and increase when the stock falls.

You can measure gamma for a single option, or aggregate it across all your positions in an underlying. This total is called position gamma.

The table below compares all the main differences between short and long gamma.

Long Gamma: Real World Example

In this example, we’re going to look at a long straddle on SMH (VanEck Semiconductor ETF) expiring in 17 days:

As we learned, all long options have long gamma, and gamma is highest at the money. This trade involves two at the money longs, so gamma is very high.

The put delta is negative because puts move opposite the stock. But the gamma is still positive; all long options are long gamma.

We start out basically delta-neutral at +0.04, right around at the money. What the 0.054 gamma tells us is that on the next $1 move in SMH, our delta will shift by about 0.054.

- If SMH goes up $1: 0.04 + 0.054 ≈ +0.09 deltas (longer stock exposure).

- If SMH goes down $1: 0.04 – 0.054 ≈ –0.01 deltas (shorter stock exposure).

That is the essence of long gamma - your stock exposure expands quickly in either direction.

At 17 days to expiration, gamma is already elevated. As time passes and the stock stays around the strike, gamma will increase further and become even more sensitive to small moves.

Long Gamma Strategies

Here are a few different long gamma strategies you can deploy based on your market outlook:

Short Gamma: Real World Example

In this example, we’re going to look at an out of the money short put spread on XLF (Financial Select Sector SPDR). We have sold the 53 put and bought the 52 put, expiring in 17 days. Here are the details for our bullish trade:

As we learned, short options have short gamma. This short put spread combines one long put and one short put, but the short side dominates, leaving net gamma negative.

We start with a net position delta of +0.14, indicating a slight long stock bias from the outset. The –0.05 gamma tells us that on the next $1 move in XLF, our delta will shift against us by about 0.05 shares.

- If XLF goes up $1: 0.14 – 0.05 ≈ +0.09 deltas (less long exposure).

- If XLF goes down $1: 0.14 + 0.05 ≈ +0.19 deltas (more long exposure).

At 17 days to expiration, the gamma risk is already meaningful. If XLF hovers near the short strike, gamma will grow even more as expiration approaches, making the position increasingly sensitive to small moves.

Short Gamma Strategies

Here are a few short gamma option strategies.

What is a Gamma Squeeze?

A gamma squeeze occurs when a very large move in the price of a stock (or any asset) forces market makers to buy or sell large amounts of the stock to hedge their open options positions.

Whenever you buy an options contract, a market maker typically takes the other side of that trade. For example, if you were to buy a 0DTE call on a meme stock, which we’ll call ABC, a market maker will have sold you that call, leaving them with upside risk exposure.

To neutralize this risk, a market maker may buy the underlying stock as the price increases to hedge their short-call position. As the stock price rises, the market maker must buy more shares to maintain a neutral delta, which can amplify the upward price movement, creating a gamma squeeze.

Gamma Hedging vs Delta Hedging

- Delta Hedging: Reduces risk from stock price movement by using a stock or option hedge, focusing more on changes in volatility.

- Gamma Hedging: Refers to the adjustments made to delta hedges (e.g., daily, weekly) to account for changes in stock prices, maintaining the effectiveness of the hedge.

A portfolio with too many positive or negative gammas can experience volatile swings in delta as the underlying asset price moves. Many traders use gamma hedging strategies to offset this risk.

While delta hedging can be achieved by buying/selling the underlying assets or options on those assets, gamma hedging is typically done purely through options.

For example, if your gamma risk is skewed positively because you have too many calls, adding put contracts will help neutralize the gamma exposure by offsetting the sensitivity to price changes in the underlying asset.

A gamma-neutral portfolio means your position has no sensitivity to changes in the rate of delta as the underlying price moves. Market makers, who often have vast inventories of options, often try to achieve a gamma-neutral portfolio to offset the risk of large price swings.

Gamma on the Options Chain

Let's conclude by taking a look at gamma and delta on the TradingBlock options chain for SPX options.

These are 0DTE (zero days to expiration) options, meaning they expire at the end of the day. With SPX trading at 6,706, the closest options to being at the money are the 6,705 and 6,710 calls and puts, so it makes sense that these strikes have the highest price sensitivity (delta) and the strongest gamma.

Notice that while both delta and gamma for calls are positive, the put options carry negative delta but still positive gamma. This is because gamma measures the rate of change in delta, and that responsiveness is always positive regardless of whether the option itself has positive or negative delta.

⚠️ Disclaimer: Gamma can amplify both gains and losses. Before trading options, be sure you understand how gamma interacts with delta, volatility, and time decay. Always review the Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options before entering any options strategy.

FAQ

A gamma squeeze occurs when market makers hedge short call positions by buying shares of the underlying asset, which drives the stock price up.

Long gamma refers to a position that benefits from large moves in the underlying because delta accelerates in your favor, such as when buying calls or puts, while short gamma refers to a position that loses from large moves because delta accelerates against you, such as when selling calls or puts.

Delta shows how fast an option’s value moves with the stock, while gamma is the horsepower that makes that speed increase or decrease.

Options traders use gamma to see how quickly delta will change as the stock moves, helping them manage risk, hedge positions, and decide whether to seek or avoid volatility.

Being long gamma means your position benefits from directional moves because delta shifts in your favor; for example, a long call option gains more quickly as the stock rises.

Gamma is negative for short options because as the underlying asset moves, delta shifts against you, making losses accelerate instead of profits.

High gamma is a good strategy for traders looking to profit from large price moves, as it increases the option's sensitivity to changes in the underlying asset.

.png)

.avif)