Short Iron Condor Options Strategy: Beginner's Guide

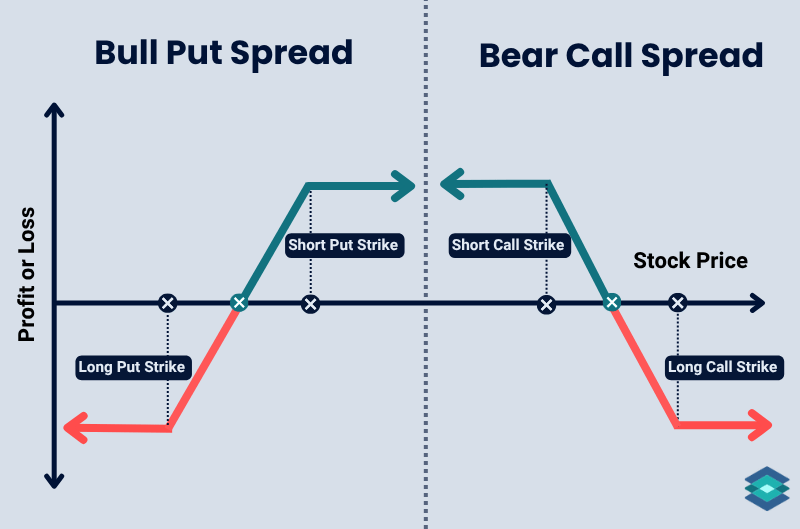

A short iron condor is a market-neutral, defined-risk options trade made up of a short call spread and a short put spread. The trade reaches max profit if the stock stays between the short call and short put strikes through expiration.

The short iron condor involves selling an out of the money call spread and an out of the money put spread, using the same expiration and equal distance between strikes. It’s a four-leg trade with limited risk and limited reward, built to take advantage of time decay and low volatility. The further out you place the strikes, the higher the probability, but the lower the credit received.

Highlights

- Risk: Capped at the width between strikes minus the credit received — max loss occurs if the stock finishes beyond one of the long options.

- Reward: Limited to the premium collected — max profit happens if the stock stays between the short call and put strikes.

- Outlook: Neutral to slightly directional — best when you expect the stock to trade within a defined range.

- Edge: Works best when implied volatility is high at entry and expected to fall — lets you sell rich premium and buy cheaper wings.

- Time Decay: Positive — theta works in your favor, especially when the stock stays quiet near expiration.

🤔 New to options? It helps immensely to understand how short call spreads and short put spreads work before advancing to iron condors.

.png)

Short Iron Condor: Trade Components

Here’s how you construct a short iron condor:

- Sell 1 put option (strike A)

- Buy 1 put option (lower strike B)

- Sell 1 call option (strike C)

- Buy 1 call option (higher strike D)

- All options share the same expiration date

This creates a defined-risk, market-neutral credit spread. You're collecting premium from both the call and put sides, betting the underlying stays between the two short strikes through option expiration.

Ideally, iron condors are opened as one trade. If you leg in, you may take on directional risk or skew your breakeven prices.

Here’s how you’d set up the short iron condor on the TradingBlock dashboard:

When to Sell an Iron Condor

Here are a few situations where it may make sense to sell an iron condor:

- Neutral Bias: You're expecting the stock to stay in a range. This option premium selling strategy benefits from time decay and minimal movement.

- High Implied Volatility: Elevated IV means richer premiums. You want to sell when IV is high and expected to fall before expiration.

- You’re Willing to Manage It: While an iron condor has capped risk, you should still be ready to manage the trade if it moves near your short strike prices. That could mean rolling one side or adjusting the entire spread to stay centered around the stock price.

Short Iron Condor: Payoff Profile

Before moving to a real-world trade example, let’s examine the max profit, breakeven, and loss scenarios for a short iron condor.

Maximum Profit Zone

The most you can make on any net credit options trade is the premium received. If you sell an iron condor on ABC for a 2.50 credit, this 2.50 ($250 total) is your max profit. This happens if, at expiration, ABC is trading between the short strikes.

Let’s say ABC is trading at $100:

- Sell the 95/90 put spread

- Sell the 95 put for 2.50

- Buy the 90 put for 1.25

- Net credit from put spread: 1.25 ($125)

- Sell the 105/110 call spread

- Sell the 105 call for 2.50

- Buy the 110 call for 1.25

- Net credit from call spread: 1.25 ($125)

- Total credit received: 2.50 ($250)

This is your maximum profit, earned if ABC stays between 95 and 105 through expiration. We can see this below:

🦋 If you expect the market to stay tighter around one strike, consider the iron butterfly. Read about it here!

Breakeven Zone

The breakeven prices on a short iron condor are found by adding and subtracting the total credit received from the short call and short put strike prices.

- Lower breakeven = short put strike minus credit received

- Upper breakeven = short call strike plus credit received

If we return to our ABC trade:

- Lower breakeven = 95 – 2.50 = 92.50

- Upper breakeven = 105 + 2.50 = 107.50

ABC must finish between 92.50 and 107.50 at expiration for the trade to be profitable, as seen below:

Maximum Loss Zone

The maximum loss on a short iron condor happens when the stock moves beyond one of the long strikes, making one spread fully in the money. Since the risk is defined, your loss is capped.

- Max loss = spread width minus credit received

In our ABC trade:

- Spread width = 5.00

- Credit received = 2.50

- Max loss = 5.00 – 2.50 = 2.50 ($250)

This $250 is also the cost of the trade.

This loss occurs if ABC finishes at or below 90 or at or above 110 at expiration, as seen below:

Short Iron Condor: Trade Example

Financial stocks have seen significant volatility in recent months. While we believe the bulk of that turbulence is behind us, implied volatility in XLF (Financial Select Sector SPDR Fund) options remains elevated. To capitalize on this, we're selling an iron condor.

I like XLF for a few reasons:

- High stock volume (usually means high option volume)

- Decent bid/ask spreads and low slippage

- Numerous strike prices and expirations

Selecting Our Options

I want to give myself some time, so I will aim for an expiration just over a month away. Let’s head to the TradingBlock dashboard to find an expiration cycle and some strike prices that work for us on the options chain:

We’re selling the 53 call and 47 put, each about 5–6% out of the money — a reasonable setup if our goal is for both options to expire worthless. To hedge, we’ll buy the 55 call and 45 put, giving us a $2-wide iron condor.

Remember, to determine our max loss and the cost of the trade, we subtract the credit received from the spread width. In this case, the spread is $2 wide, and we’re collecting $0.34, so our max loss is $1.66 ($166 total), and that’s also our margin requirement.

Always send your trade at the midpoint and use limit orders on options. If you don’t get filled immediately (and want to), walk your order down in penny or nickel increments until you do. And if you can’t get a decent fill, skip the trade. You can learn more about options trading liquidity metrics here.

We’ll assume we got filled at the midpoint on this one, which means we received a credit of 0.34:

XLF Trade Details

And here are the details of the trade we just put on:

- Current XLF Price: $50.36

- Expiration: 38 days

- Sell 47 Put @ $0.39

- Buy 45 Put @ $0.22

- Sell 53 Call @ $0.22

- Buy 55 Call @ $0.04

- Net Credit Received: $0.34 ($34 total)

- Lower Breakeven = 47 – 0.34 = $46.66

- Upper Breakeven = 53 + 0.34 = $53.34

- Max Profit: $0.34 ($34 total)

- Max Loss: $2.00 – 0.34 = $1.66 ($166 total)

- Profit Range: $46.66 to $53.34

- Max Profit Zone: Between $47 and $53 at expiration

- Risk/Reward: Risking $166 to make $34

- Margin Requirement: $200 – $34 credit = $166

Short XLF Iron Condor: Winning Outcome

Thirty-eight days have passed, and expiration is here. XLF moved around a bit, but ultimately closed at $52, within our short strikes.

- XLF Price: $50.36 → $52.00 ⬆️

- Expiration: 38 days → 0

- Sell 47 Put @ $0.39 → $0.00

- Buy 45 Put @ $0.22 → $0.00

- Sell 53 Call @ $0.22 → $0.00

- Buy 55 Call @ $0.04 → $0.00

- Final Value: All four legs expired worthless

- Net Gain: $0.34 ($34 total)

- Percent of Max Profit Realized: 100%

The stock rallied over 3%, yet our market-neutral trade still profited. We would be in trouble if we sold our options 2% out of the money rather than 5%.

Let’s see how the trade played out.

XLF Winning Trade: Under the Hood

As we can see above, the journey to our options expiring worthless wasn’t as smooth as the final outcome suggests. With around six days to expiration, our short 53 call was trading near $4.

But remember, we were hedged with the 55 call, which was trading for about $2 at the time. Since this is a two-point spread, the most we could ever lose is the width of the spread ($2) minus the premium we collected.

- If we had exited then, we would’ve paid just under $2 to close it

- Subtracting our $0.34 credit, the loss would’ve been $1.66

The most we could’ve made was $0.34, while the most we could’ve lost at this point was $1.66 — nearly 5 times greater than our potential reward, or a 388% larger loss than the max profit.

Assignment Risk

We also would’ve likely been assigned to our short call option around 6 DTE, which could’ve forced us to liquidate the call side of the trade, leaving us exposed to only the put spread.

Remember, the odds of being assigned on American-style options increase when:

- There’s little time left until expiration

- The option is deep in the money and mostly intrinsic value

Short XLF Iron Condor: Losing Outcome

XLF didn’t go our way in this trade outcome. Volatility spiked, sending the stock lower while increasing implied volatility, pushing up the value of our short put even more. Here’s where things ended:

- XLF Price: $50.36 → $42.00 ⬇️

- Expiration: 38 days → 0

- Sell 47 Put @ $0.39 → $5.00

- Buy 45 Put @ $0.22 → $3.00

- Sell 53 Call @ $0.22 → $0.00

- Buy 55 Call @ $0.04 → $0.00

- Final Value: Put spread = $2.00 wide → fully in-the-money

- Net Loss: $2.00 – $0.34 credit = $1.66 ($166 total)

- Percent of Max Loss Realized: 100%

Now let’s get into the weeds with this trade:

XLF Losing Trade: Under the Hood

As we can see, this trade turned against us almost as soon as we put it on.

Our calls went worthless almost immediately, but implied volatility jumped, and the stock tanked, sending both of our put options soaring.

Had we just been short the 47 put without hedging it with the 45 put, our loss would’ve been $5.00 ($500 total) with XLF closing at $42. But our max loss was capped because we bought the 45 put for protection.

⚠️Remember: You can never lose more on an iron condor than the width of the spread minus the premium collected.

In this case:

- Spread width: $2.00

- Credit received: $0.34

- Max loss = $2.00 – $0.34 = $1.66 ($166 total)

Even though volatility exploded and the stock collapsed, our risk was defined.

But again, this trade likely would not have survived intact until expiration. As with our previous trade, we can see that one leg, our short 47 put, was deep in the money in the days leading up to expiration. This would have almost certainly led to an early assignment.

Choosing Your Deltas

In options trading, delta is the option Greek that refers to how much an option's value may change given a $1 move up or down in the underlying asset. Delta also tells us:

- The number of shares an option ‘trades like’

- The probability an option has of expiring in the money

We’re going to focus on the latter of these two bullets.

What Delta Tells Us

If a call option has a delta of 0.15, there's about a 15% chance it finishes in the money. Since we’re net short in an iron condor, we want our short strikes to expire out of the money, so naturally, we’d prefer lower deltas.

But low deltas come with low premiums. So you need to find the sweet spot between getting paid enough to make the trade worth it and not taking too much risk. Delta is a solid tool for managing that balance.

Delta also tells us the total directional exposure of the trade. When the iron condor is put on, it should have net delta close to zero, give or take a few points. That’s because the bullish and bearish sides of the trade are designed to offset each other. The structure is off if your net delta is too far from zero at entry. You’re not trading a neutral range anymore, you’re directional.

Let’s now explore selecting deltas for your short and long options in the short iron condor trade.

Short Options Delta Selection

- Somewhere between 16 and 25 delta

- Low enough to stay out of trouble most of the time

- High enough to collect meaningful premium, ideally at least $1.00 on a 5-point wide iron condor

If I go much lower than 16, I’m barely collecting anything. Go too high, and I’m back in strangle territory. For me, 20–25 delta is usually the pocket that gives the best mix of premium, probability, and peace of mind.

Long Options Delta Selection

- I typically place these around 5–10 delta

- The goal is to cap the risk, not pay too much for them

- I don’t want to overpay on insurance, but I do want it there.

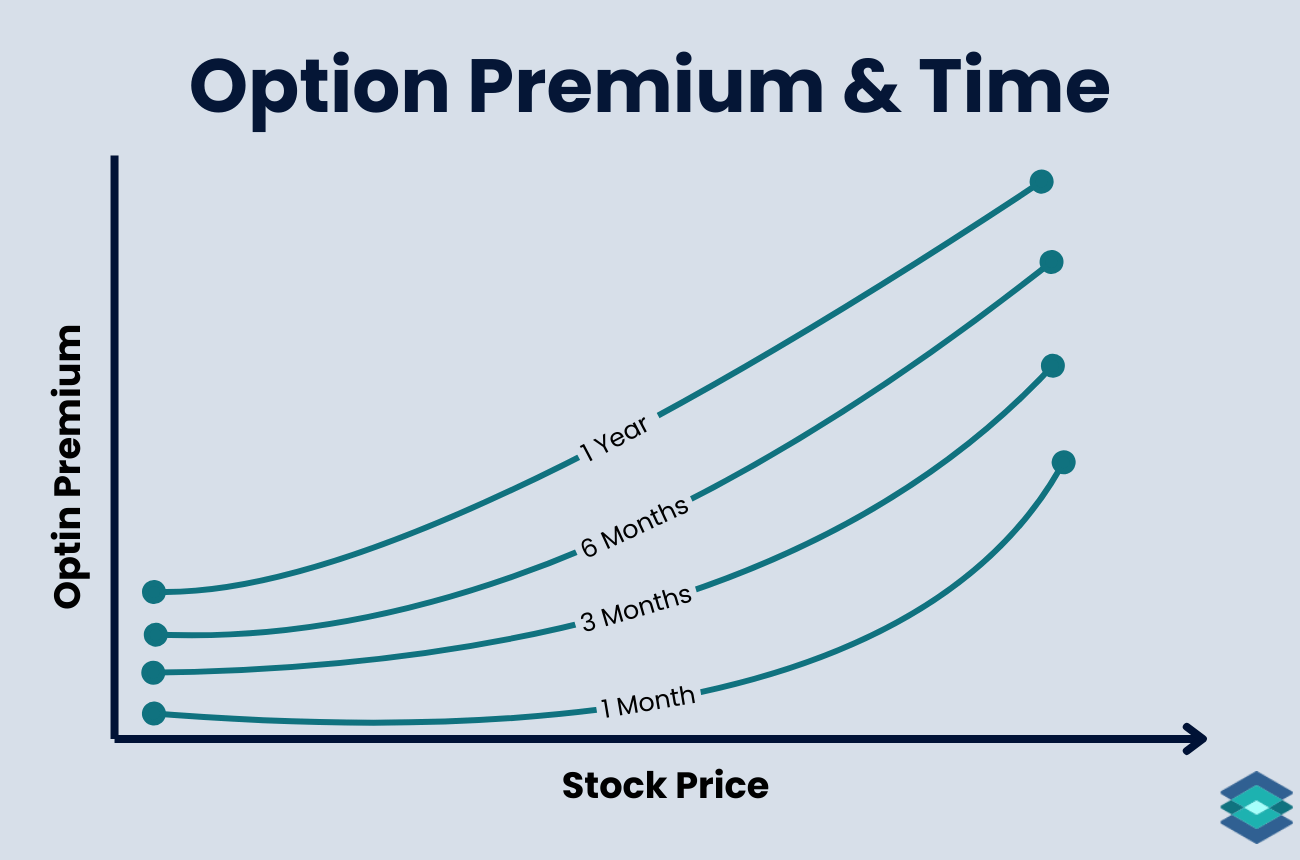

Time Decay and Theta

Option premiums gradually lose value in a stable market, where the underlying stays within a defined range and implied volatility remains steady. As net sellers, this time decay works in our favor.

The closer we get to expiration, the faster that decay accelerates. Since the short strikes carry more premium than the long wings, the position benefits as the trade structure contracts in value.

.png)

Theta and Iron Condors

Theta is the option Greek that reflects time decay. It tells us how much value the option is expected to lose each day.

The short options in our iron condor have higher theta than the long options, meaning they lose value faster as time passes.

This difference makes theta net positive, which means you're collecting time decay overall.

What to look for:

- A positive net theta (e.g., +0.08 to +0.15) is ideal.

- The highest theta comes when the stock is between your short strikes, and close to expiration.

- Avoid trades where the long wings eat up too much premium, as this will reduce your net theta advantage.

Implied Volatility and Short Iron Condors

Short iron condors benefit when implied volatility is high at entry and then falls. Elevated IV means richer premiums, giving you more room between strikes and a higher potential credit. As IV drops, the options lose value faster, helping the trade profit even if the stock doesn’t move.

Things to know:

- High IV = better credit

- Falling IV helps: Even if price doesn’t move, a drop in IV can reduce your position’s value.

- Neutral bias works best: This is a market-neutral strategy: you want the stock to stay between the short strikes.

- Closer to expiration = more vega sensitivity: The trade becomes less affected by changes in IV as expiration nears.

Iron Condors: Strike Selection

You can set the short strikes of your iron condor based on your expected move or range for the underlying. The wider the spread (i.e., the further out of the money the short strikes), the higher the probability of profit, but also the greater the max potential loss, since you’re collecting less premium.

Some traders set short strikes using standard deviation ranges. This takes the guesswork out of the equation.

- One standard deviation (~15–20 delta): about 68% probability the stock stays within your range.

- Two standard deviations (~5–10 delta): about 95% probability, but much lower premium.

Remember, delta tells us the percent chance that an option will expire in the money. For example, if an option has a delta of 0.07, that means it has about a 7% chance of finishing in the money at expiration and a 93% chance of expiring worthless.

3 Risks of Short Iron Condors

The short iron condor is a four-legged trade, so if you’re not willing to actively monitor and adjust your position, this strategy probably isn’t for you. Here are a few risks to keep in mind:

1. Assignment Risk

American-style options (all stocks and ETFs) have early assignment risk on the short sides, especially if one of your short strikes goes in the money near expiration. This is most common when there's little extrinsic value left or an upcoming dividend. Being assigned early can throw off your risk profile and lead to unintended stock positions.

2. Breakout Risk

This is a rangebound strategy. If the stock makes a big move outside your short strikes—either up or down—you’re at risk of max loss. This can happen fast in earnings season, on news events, or during periods of high volatility. Always be aware of the catalysts that could send the stock running.

3. Liquidity Risk

Options on thinly traded stocks or ETFs can have extremely thin markets. Signs of low liquidity include:

- Wide bid/ask spreads

- Low open interest

- Low volume.

If you're trading illiquid strikes, you will likely have issues getting filled at a decent price, particularly when volatility jumps. Read more about option liquidity in our dedicated article.

Iron Condors and The Greeks

In options trading, the Greeks are a set of risk metrics that help estimate how an option’s price will respond to changes in key market variables. Here are the five most important Greeks to know:

- Delta – Measures how much the option price moves relative to the underlying stock.

- Gamma – Tracks how Delta changes as the stock moves.

- Theta – Measures time decay, showing how much value the option loses daily.

- Vega – Sensitivity to implied volatility, affecting option price.

- Rho – Measures impact of interest rate changes on the option price.

And here is the relationship between short iron codors and these Greeks:

Iron Condor Calculator

Check out our iron condor calculator below to visualize different trade outcomes!

⚠️ Short iron condors involve defined risk, but still require a solid understanding of multi-leg option strategies. This trade may not be appropriate for all investors. Profitability can be affected by commissions, fees, and slippage—none of which are reflected in the examples above. Be sure to read The Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options before trading.

FAQ

A long iron condor is a net debit strategy that profits when the stock moves sharply outside the outer strikes; it’s a long volatility play. The short iron condor is a market-neutral credit trade that profits when the stock stays between the short strikes, ideally moving as little as possible.

Condor: Uses only calls or only puts. You buy one option, sell two closer to the money, and buy another further out.

Short Iron Condor: Combines calls and puts. You sell one call and one put, then buy further out calls and puts to limit risk.

Key Difference: Condors use one option type, while iron condors use both.

A short iron condor is selling a call and put option, and then buying a further out-of-the-money call and put option (with the same width). It can also be thought of as selling two vertical spreads - a call spread and a put spread.

A long iron condor is simply buying a call and put option, and then selling a further out-of-the-money call and put option (with the same width). It can also be thought of as buying two vertical spreads - a call spread and a put spread.

To calculate the breakeven on a short iron condor:

- For the lower side, add the net credit to the lower short strike.

- For the upper side, subtract the net credit from the higher short strike.

The maximum loss on a short iron condor is calculated by subtracting the credit received from the width of the spread, then multiplying the result by 100.

.png)