Short Straddle Options Strategy: Beginner's Guide

The short straddle is a market-neutral, high probability net credit trade that involves selling a call and a put at the same strike price and expiration cycle. The maximum profit, equal to the credit received, is rarely realized, while the maximum loss is significant and even unlimited on the uncovered short call side.

The short straddle is a high-risk options trade designed to profit if the underlying asset—whether a stock, ETF, or index—stays close to the strike price. To be profitable, the underlying must stay within a range defined by the strike price plus or minus the total credit received by expiration.

Highlights

- Risk: Unlimited on the call side; substantial on the put side. One big move can wreck the trade.

- Reward: Max profit is the credit received — captured only if the stock pins the strike at expiration.

- Outlook: Neutral — works best when the stock goes nowhere and IV drops.

- Edge: Short straddles benefit from rich premiums and fast time decay.

- Time Decay: Strongly favorable — theta accelerates the closer you get to expiration.

- Approximate Profitability: Generally greater than 50%.

🤔 New to options? It helps immensely to understand both the short put and short call strategies before jumping into straddles.

Short Straddle Trade Components

Here’s how you construct a short straddle:

- Sell 1 call option

- Sell 1 put option (same strike)

- Both options are the same expiration date

- Generally, both options are at the money (not always)

This creates a market-neutral net credit position with no directional bias. You're collecting option premium on both sides, betting the underlying stays near the strike price through expiration.

Ideally, straddles are put on in one trade. If you leg in, you may have directional price risk. Here is how you set the short straddle up on the TradingBlock dashboard:

Market Outlook: When to Sell a Straddle

Here are a few scenarios where it may make sense to sell a straddle:

- Neutral Bias: This one’s obvious—the short straddle is one of the best strategies to profit from a flat market.

- High Implied Volatility: High implied volatility (IV) inflates the price of all options. Sell a straddle when the implied volatility (IV) is elevated, but only if you expect it to decline before your options expire.

- You’re Willing to Adjust: Since the short straddle involves selling two options, one will almost always be in the money at any given time. That means high assignment risk, especially the deeper it goes and the closer expiration becomes. Be ready to roll a leg to avoid an assignment or restructure your trade.

Short Straddle Payoff Profile

And now let’s break down the maximum profit, breakeven points, and maximum loss for this trade.

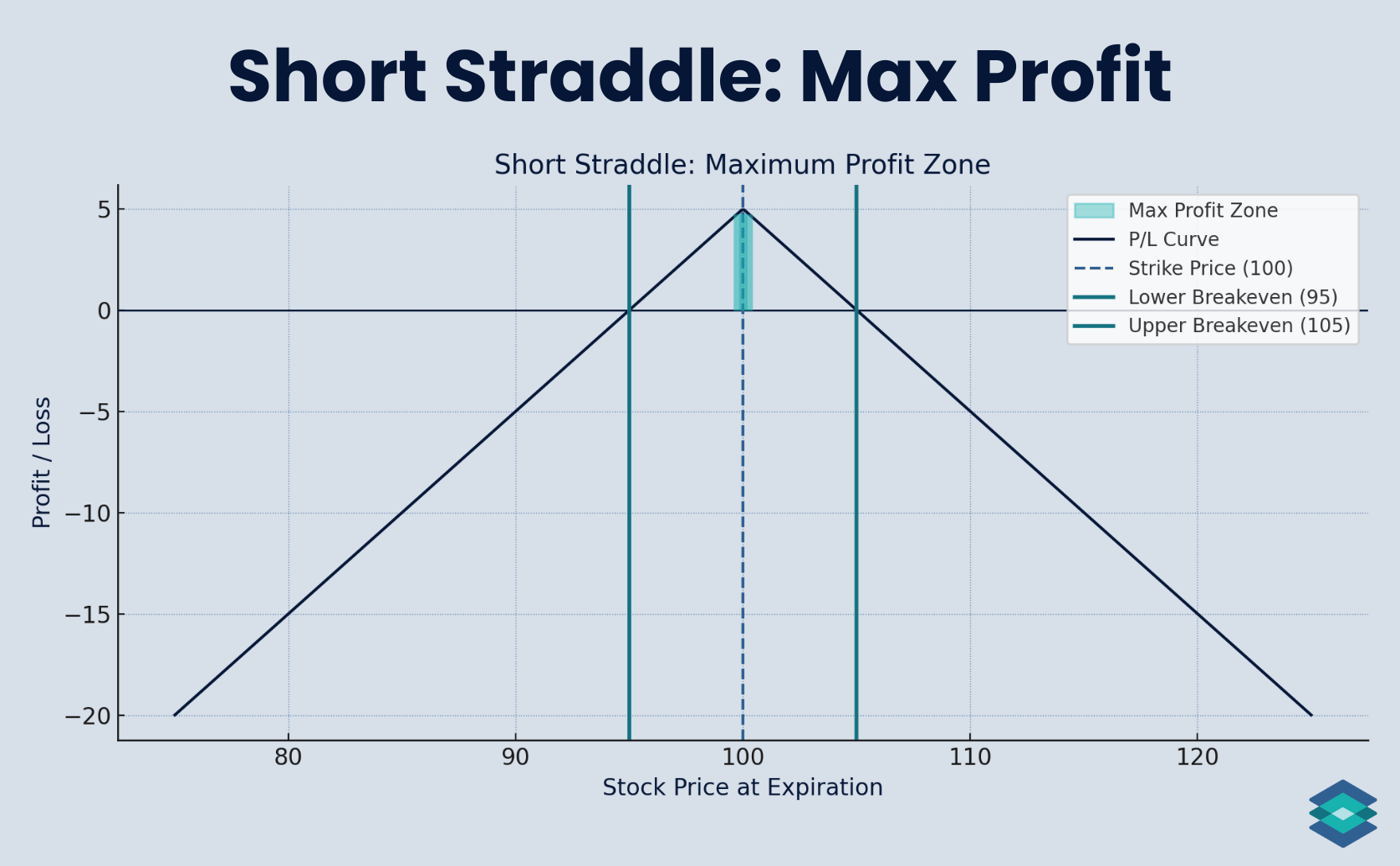

Maximum Profit Zone

The max profit on a short straddle is:

Max Profit = Total Credit Received

This outcome occurs when the underlying asset's price equals the strike price of the options sold on expiration.

For example, let’s say we sell both the 100 strike call and the 100 strike put on ABC for a combined credit of $5.00:

- Sell the 100 call for $2.50

- Sell the 100 put $2.50

- Total credit received: $5.00 ($500)

We earn the full $500 only if ABC closes exactly at $100 at expiration. The odds of this happening are incredibly slim.

Additionally, if you’re trading American-style options, you’ll probably have to close one or both legs early because of assignment risk. Even if the stock closes right at the strike price, there’s a 50/50 shot you’ll get assigned on the call, the put, or both, creating a lot of stock risk.

Breakeven Zone

A short straddle has two breakeven points, one on the upside and one on the downside. Here’s how you calculate them:

- Upper Breakeven = Strike Price + Total Credit Received

- Lower Breakeven = Strike Price – Total Credit Received

Going back to our previous example:

We sold the 100 strike price call and 100 strike price put on ABC for a total credit of $5.00.

That gives us:

- Upper breakeven = 100 + 5 = 105

- Lower breakeven = 100 – 5 = 95

If ABC closes between $95 and $105, the trade is profitable. But if it finishes above 105 or below 95, losses start building.

Maximum Loss Zone

The maximum loss on a short straddle is unlimited. The call side has infinite loss potential since there’s no cap on how high a stock can go. The put side also carries substantial risk because, theoretically, a stock can fall to zero.

Here’s how that breaks down:

- Call Side: Max Loss = ∞

- Put Side: Max Loss = Strike Price – Total Credit Received

Going back to our ABC example:

- Strike price: 100

- Total credit received: $5.00

- Breakeven range: 95 to 105

Let’s see what happens under a couple of different scenarios:

If ABC collapses to $80 at expiration:

- Your short put is $20 in the money

- Subtract the $5.00 credit

- Loss = 20 – 5 = $15, or $1,500

If ABC rallies to $120:

- Your short call is $20 in the money

- Subtract the $5.00 credit

- Loss = 20 – 5 = $15, or $1,500

Short Straddle Margin Requirements

Since a stock can only finish above or below a strike price — never both — it wouldn’t make sense for brokers to require full margin on both the call and the put for short straddles.

Therefore, most brokers charge margin based on the riskier side of the trade. Additionally, the premium received from the less risky leg is usually added to the margin requirement

For example, let’s say you sell the 95 straddle on ABC for a net credit of $1.75. Here’s where the premium came from and the individual margin requirements:

- Short 95 put = $1.00 → $1,700 margin requirement

- Short 95 call = $0.75 → $1,600 margin requirement

The margin requirement here will be based on the higher of the two options — in this case, the short put leg at $1,700.

Next, brokers typically add the premium from the other leg (the $75 call credit), bringing your total margin requirement to:

$1,700 + $75 = $1,775

Short Straddle: Moneyness and Skew

Most short straddles are sold at the money, meaning the strike price matches the stock’s current price. But straddles can be sold at any level of moneyness.

For example, if ABC is trading at $100 but you’re confident it’ll pin at $105 near expiration, you could sell the 105 straddle instead. This creates a more directional setup than a standard at-the-money straddle.

Professional traders refer to this as “skewing the straddle.” You’re still selling the same strike call and put, just not where the stock is trading. When you do this, your trade leans bullish or bearish, depending on the skew.

For example:

- Bullish skew: Sell the 105 straddle when stock is at 100

- Bearish skew: Sell the 95 straddle when stock is at 100

Short Straddle: SMH Trade Example

The market’s been in free-fall mode lately. Because of that, implied volatility is up across the board, especially in the semiconductor sector.

Over the next 30 days or so, I believe that semiconductors are likely to stay right where they are. Earnings aren’t out for another two months, and I think options are priced too high.

To take advantage of this, I’m going to sell an at the money straddle on the VanEck Semiconductor ETF (SMH). Here’s why I chose SMH:

- Broad-based semiconductor exposure

- Decent bid/ask spreads and high options volume

- Numerous strike prices and expirations

Let’s head over to the TradingBlock dashboard and find an expiration and strike price that works for us:

SMH: Trade Setup

.png)

Notice on the above options chain how high the premiums are for these options. At the money options are always priced higher than out of the money ones, and because of their rich premiums, the bid ask spreads can be wide. These contracts also carry high implied volatility (which we love as net sellers!), which cranks up the option prices and the spread widths even more.

That’s why it’s crucial to use limit orders when trading options. Always start at the midpoint. If you don’t get filled right away (and want to), walk your order down in penny or nickel increments until you do. And if you can’t get a decent fill? Skip the trade.

We will assume we got filled at the mid-point on this trade, which means we brought in a credit of 20.47. We can see this below.

.png)

Trade Details:

And here are the details of the trade we just put on:

- SMH Price: 212.30

- Expiration: 35 days

- Sell 212.5 Call @ $10.65

- Sell 212.5 Put @ $9.82

- Net Credit Received: $20.47 ($2,047 total)

- Breakeven Prices: 212.50 ± 20.47 = $192.03 / $232.97

- Max Profit: $20.47 ($2,047 total)

- Max Loss: Unlimited (upside) / $19,203 worst-case (downside to $0)

- Margin: $4,226

The most we can make here is $2,047, the premium we took in. We break even with SMH trading at $192.03 on the downside or $232.97 on the upside — and we earn a partial profit anywhere between those two levels. The closer SMH finishes to $212.50, the more premium we keep.

Bear in mind the high margin requirement for this trade. With the risk-free rate currently around 4%, don't forget to factor in that opportunity cost when making your trade.

Let’s now explore a few different outcomes!

Short SMH Straddle: Winning Outcome

Thirty-five days have passed, and expiration is upon us. After an early scare, SMH settled down to $212 a share, netting us a modest profit of $1,997.

The 212.5 call expired worthless, and the 212.5 put finished just $0.50 in the money, costing us $50. This wasn’t a max profit outcome, but capturing 97.6% of max profit is about as good as it gets with short straddles.

Here’s where we ended:

- SMH Price: $212.30 → $212.00 ⬇️

- Expiration: 35 days → 0

- Sell 212.5 Call @ $10.65 → $0.00

- Sell 212.5 Put @ $9.82 → $0.50

- Final Value: $0.50 loss on the put

- Net Profit: $20.47 – $0.50 = $19.97 ($1,997 total)

- Percent of Max Profit: 97.6%

- The call expired worthless = $0.00 ✅

- The put expired $0.50 in the money = $0.50 loss

- We collected $20.47 total in premium

- Final Profit = $20.47 – $0.50 = $19.97 per share → $1,997 total

This is an ideal—albeit unlikely—trade outcome. I say unlikely because there's a good chance we would’ve been assigned on one of our options, probably the short put, in the days leading up to expiration.

But we’ll cover assignment risk in detail later. For now, let’s just assume assignment didn’t happen.

This outcome is about as good as it gets. You’re rarely going to hit max profit on a short straddle, but we came close, capturing over 97% of the premium.

I would’ve closed the trade once I hit a 50% profit, which happened around 8 days to expiration. That final week is when assignment risk ramps up. With less extrinsic value left, the counterparty has more incentive to exercise.

That’s why many traders set profit targets (buy limit orders for short straddles) well before expiration—it’s often not worth chasing the last few dollars of premium if it means taking on unnecessary risk.

Short SMH Straddle: Losing Outcome

In this trade outcome, SMH tanked, sending our short put value skyrocketing:

Here’s where the trade finished:

- SMH Price: $212.30 → $180.00 ⬇️

- Expiration: 35 days → 0

- Sell 212.5 Call @ $10.65 → $0.00 ✅

- Sell 212.5 Put @ $9.82 → $32.50 ❌

- Final Value: $32.50 put value

- Net Profit: $20.47 – $32.50 = –$12.03 (–$1,203 total)

Halfway through the trade, SMH was trading right at $212.50—our straddle strike—and we could have bought back the trade for around $12. That would’ve locked in a $8.47 profit, or $847 total.

But we rolled the dice, and SMH kept sliding. By expiration, our short put was fully in the money, worth $32.50, which is all intrinsic value. This put would have been assigned many days before expiration in the real world. The call expired out of the money or worthless.

This was a bad outcome, no question. But considering how far SMH dropped, we weren’t totally wiped out. That $20.47 in premium gave us a wide cushion, pushing our breakeven levels down to $192.03 and up to $232.97.

As a rule of thumb, many traders close short straddles when their losses approach 2x the credit collected. In this trade, that number was about $40.94. We didn’t hit it, but we got close at $32.50.

Another rule is to take profits at 25–50% of max gain, which we hit halfway through the trade life cycle.

Choosing Your Deltas

In options trading, delta is the option Greek that refers to how much an option's value may change given a $1 move up or down in the underlying asset. Delta also tells us:

- The number of shares an option ‘trades like’

- The probability an option has of expiring in the money

We’re going to focus on the latter of these two bullets. Since at the money options have a 50% chance of expiring in the money, their deltas will hover around 0.50, or “fifty” as we say in the trading world.

This is assuming that the underlying stock will be trading at exactly the strike price when you put on the trade, which is not exactly the case. Personally, I widen this window to include deltas in the 0.45-0.55 range when selling my straddles. If the put is over 0.50 delta, the call will likely be under by the same amount, and vice versa.

It is also important to note that at the money options have greater risk because of their proximity to the current stock price, leading to greater sensitivity to price movements (higher gamma).

Short Straddles and Time Decay (Theta)

At the money options have the highest time decay, or ‘theta’, of all options. Since we are selling both at the money calls and puts here, this trade collects a ton of theta. As long as the stock price stays close to the strike price (and assuming implied volatility stays the same), this trade profits very nicely from the passage of time.

I aim for 0.10–0.30 theta for 0.45–0.55 delta straddles. This allows for robust daily time decay, especially in high-IV environments with elevated premiums.

Short Straddles and Expiration Selection

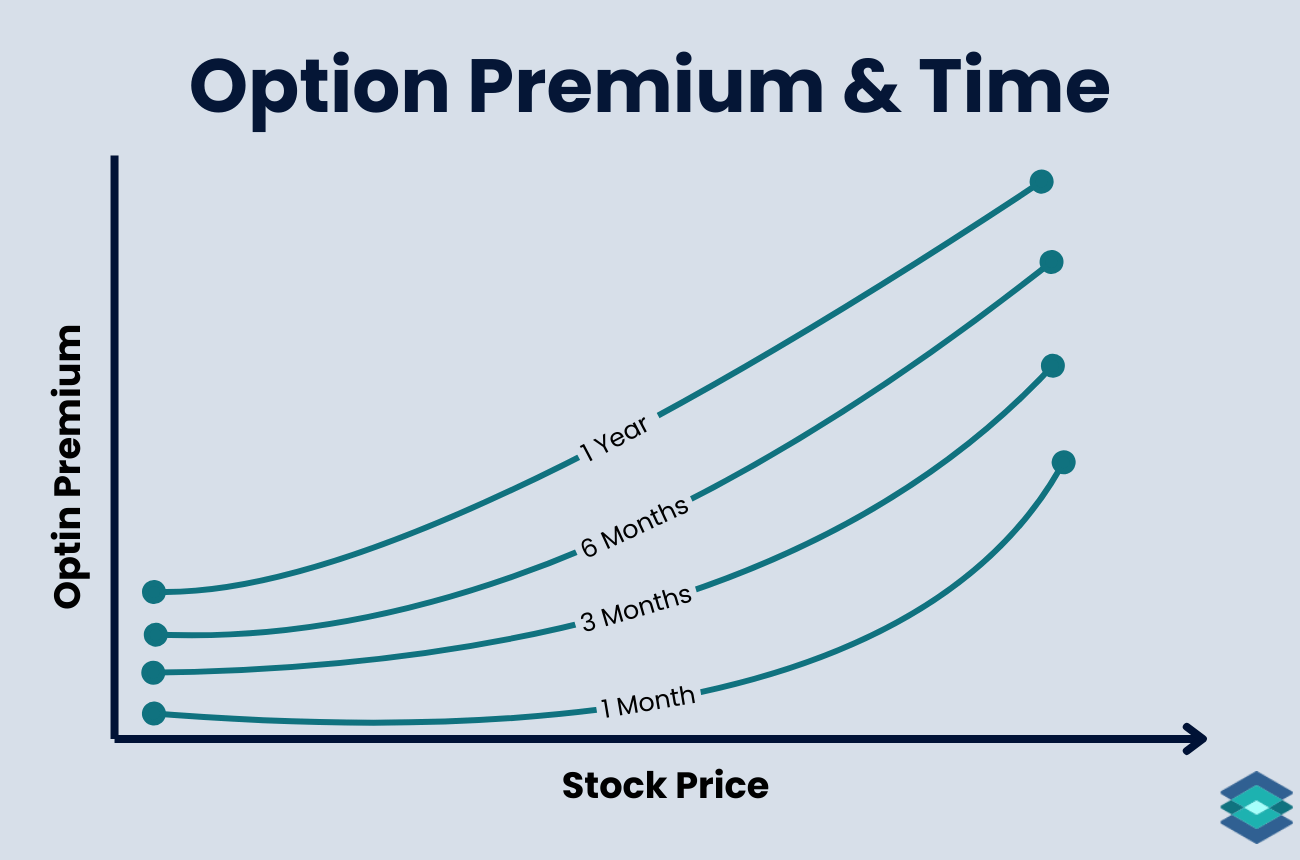

Choosing how far out to sell a short straddle (days to expiration, or DTE) is critical for balancing premium collection, time decay, and risk exposure. Time decay begins to accelerate around the 30–45 DTE mark.

.png)

Therefore, look for options within this range when selling your straddle. If you go out too far, you’ll wait a while for time decay to kick in, while this high-margin trade ties up your funds. If you don’t have enough time, you won’t be able to make adjustments to your trade.

Short Straddles and Implied Volatility

Implied volatility (IV) significantly impacts short straddles. IV drives option premiums and the trade's potential profitability. Selling straddles in high-IV environments maximizes premium collection, while low-IV settings require caution due to tighter breakeven points.

- Target High IV (IVR > 50): Sell 0.45–0.55 delta straddles when IV rank (IVR) exceeds 50, as inflated premiums widen breakeven points and increase profit potential if IV falls.

- Manage in Low IV (IVR < 25): In low-IV environments, premiums are smaller, reducing the risk-reward appeal. Consider shorter DTE (e.g., 30 days) or shift to lower delta strategies.

Long Straddle vs Short Straddle

The long straddle is a volatility bet—you’re hoping for a big move in either direction. A short straddle is the opposite, profiting with little price movement.

- Long straddle: Buy a call and put at the same strike. High risk, unlimited upside, but you need a big move to win.

- Short straddle: Sell a call and put at the same strike. Limited reward, unlimited risk—but high probability of profit if the stock goes nowhere.

Short Straddle vs Short Strangle

.png)

The short straddle and short strangle are very similar option strategies, with one huge difference: the straddle involves selling options at the same strike price. In contrast, the strangle involves different strike prices, both out of the money. Strangles, therefore, are better if you forecast more movement than the straddle, but not too much. These trades give you some margin for error.

Here’s a table comparing the two option strategies.

Managing a Short Straddle

Short straddles almost always involve active management. This is one of those trades that requires a lot of supervision.

Take Profits Early

If your short straddle is up 25–50%, consider closing it. Don’t wait for max profit—one sharp move can wipe you out. It’s best to set a buy-to-close limit order as soon as the trade is opened.

Roll the Losing Side

Once one leg goes deep in the money, you’re directional. Roll that leg up or down to a new strike or expiration to recenter the trade or reduce delta. This resets risk and keeps you in the trade, just make sure you're being paid adequately for the risk!

Watch for Assignment

Short straddles carry very high assignment risk, especially in the final week. You're exposed if one leg is in the money and the other is worthless. Avoid holding into expiration unless you’re okay managing the stock. If you're trading European-style options, like SPX, VIX, or NDX, assignment risk will not be an issue.

Roll Both Legs Out

If you need more time or want to stay delta neutral, roll the entire straddle forward as one four-way trade. This can give the trade time to work, especially if IV stays elevated.

4 Risks of Short Straddles

As I mentioned, the short straddle is a high-risk trade reserved for advanced traders. Here are a few things to watch out for:

1. Unlimited Upside Risk

If the stock rallies hard, the short call can cause unlimited losses. Since there is no cap on how high a stock can go, your loss on the short call side is theoretically infinite.

2. Early Assignment

American-style options can be exercised anytime. That means you could wake up long or short stock before you’re ready. It’s most common near expiration when extrinsic value is low. Also keep an eye on dividends as in the money short calls are typically assigned around the ex-dividend date.

3. IV Crush Doesn’t Save You

Even if volatility falls, you’re still exposed to directional risk on this trade. Keep a close watch on your two breakevens and be ready to adjust.

4. Liquidity Risk

Options on thinly traded stocks or ETFs can have extremely thin markets. Signs of low liquidity include:

- Wide bid/ask spreads

- Low open interest

- Low volume.

If you're trading illiquid strikes, you will likely have issues getting filled at a decent price, particularly when volatility jumps. Read more about option liquidity in our dedicated article.

Short Straddles and The Greeks

In options trading, the Greeks are a series of risk tools that hint at the future price of an option based on changes in different variables. Here are the 5 most important Greeks to know:

- Delta – Measures how much the option price moves relative to the underlying stock.

- Gamma – Tracks how Delta changes as the stock moves.

- Theta – Measures time decay, showing how much value the option loses daily.

- Vega – Sensitivity to implied volatility, affecting option price.

- Rho – Measures impact of interest rate changes on the option price.

And here is the relationship between short straddles and these Greeks:

⚠️ Short straddles are advanced, high-risk trades. They carry unlimited loss potential on the call side and substantial downside risk on the put side. This strategy is not suitable for all investors. Trade outcomes can be significantly impacted by assignment risk, commissions, fees, and slippage—none of which are reflected in the examples above. Always read The Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options before trading.

FAQ

The short straddle is a strong premium-selling strategy if you expect the stock to stay near the strike. It performs best in high-IV environments with limited expected movement. It’s high risk, but high probability.

The main risks are price movement and rising implied volatility. If the stock moves beyond the credit collected, losses multiply. Rising volatility alone can also inflate losses, even if the stock doesn’t move.

Sell straddles when implied volatility is elevated and likely to fall. A good rule of thumb is to take profits when you reach 25-50% of max profitability.

You sell a call and a put at the same strike and expiration, collecting a net credit. The goal is for the stock to pin that strike by expiration. Any move away from the strike price reduces your profit.

You’re short two naked options with no hedge so the short straddle is very risky. One side almost always ends up in the money, and there’s unlimited risk on the call side.