Short Call Options Strategy: Beginner’s Guide

The short call is an undefined-risk, high-probability, market-neutral to bearish options strategy with unlimited loss potential.

Short call options are bearish to market-neutral trades that profit when the underlying stock, ETF, or index stays below the strike price. Traders use them to collect premium income, but they come with unlimited loss potential if the price moves too high.

Highlights

Market Outlook: When to Sell Calls

The best time to sell a naked call option is when you are neutral to bearish on the underlying stock, ETF, or index that has elevated implied volatility (IV).

But you don’t want to be too bearish—when you sell a call naked, your max profit is limited to the premium collected. If you are expecting a substantial price decline, you may want to consider shorting stock or a long put position (long put option or bear put spread), as the reward will be higher.

You also should avoid selling calls when IV is too low. Since you are taking on substantial risk when you sell options naked, you want to be compensated for this risk in the premium collected.

But high IV is a double-edged sword—you're collecting more premium for a reason, as the market is telling you there will likely be significant price movement in the future.

Let’s review a few pertinent details about the short call options trade and then dig in.

- Ideal outlook: Slightly bearish to market neutral.

- Too bearish? Consider a long put or bear put spread instead.

- Volatility matters: Low IV = lower premiums; high IV = more risk.

- Out-of-the-money (OTM) calls: Lower premium but higher probability of success.

- At-the-money (ATM) calls: Higher premium but greater risk of getting assigned.

Short Call Payoff Profile

Selling a call option has limited upside and unlimited risk. Here's how the short call payoffs look:

Max Profit

The max profit when you sell any option is the premium you collect. It doesn’t matter how far the stock moves in your favor—your profit is capped at this credit.

For example, let’s say you sold the 95 strike price call on ABC for a credit of $0.75 ($75) while the stock is trading at $90/share. Here’s the setup:

- Stock Price: $90

- Short Call Strike Price: $95

- Premium Collected: $0.75

- Max Profit: $75 (the premium collected)

If on option expiration the stock is below $95, your short call expires worthless. It doesn’t matter if the stock is at $90, $85, or even $10—as long as it’s below the $95 strike, you keep the full premium. Your max profit is locked in at $75.

Max Loss

The risk on a naked short call is unlimited because there’s no cap on how high a stock can go.

Let’s return to our previous ABC trade to see how this works:

- Stock Price: $90

- Strike Price: $95

- Premium Collected: $0.75

- Max Loss: Infinite

There was an acquisition, and ABC skyrocketed to $135/share on expiration.

- Stock Price: $90 → $135

- Strike Price: $95

- Option Price: $0.75 → $40.00

With the stock rallying to $135 on expiration, our short call is $40 in the money. That means we’ve lost $4,000, offset slightly by the $75 premium we collected—so the net loss is $3,925.

If the stock went up to $150 instead, our loss would be $5,000 – $75 = $4,925. That’s a lot of risk, considering the maximum profit on this trade was only $75!

🤔 Want downside exposure with defined risk? Read about bear call spreads here!

Breakeven

To calculate the breakeven on a short call, just add the premium collected to the strike price:

Breakeven = Strike Price + Premium Collected

Let’s return to our previous example:

- Strike Price: $95

- Premium Collected: $0.75

- Breakeven: $95 + $0.75 = $95.75

If ABC closes at $95.75 on expiration, you don’t make anything—but you don’t lose anything either.

📖 Short Puts: Beginner's Guide

Trade Example: Short SPY Call

In our example, we will sell an out of the money call option on SPY (SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust), expiring in 39 days. We will target a call that sits around 5% out of the money.

We chose this ETF because SPY offers:

- Broad market exposure

- High liquidity (tight spreads, high volume and open interest)

- Numerous strike prices and expirations

SPY Options Chain

Let’s go to the TradingBlock platform to find a call option that works for us on the SPY options chain:

We decided to sell a 600 strike price call option expiring in 39 days for a credit of 2.28 ($228). Here are our trade details:

Our SPY Position

- Position: Short 1 SPY Call Option

- Premium Collected: $2.28 ($228 total)

- Expiration: 39 days

- Strike Price: $600

- Current Stock Price: $573.87

- Breakeven Price: $602.28

- Margin Requirement: $8,864

We sold this call option for $2.28, which means we’ll pocket the full $228 if SPY stays below $600 on option expiration. Our breakeven is $602.28 — anything above that, and we’re in the red.

This trade has limited reward and unlimited risk. We’re collecting a small premium in exchange for taking the other side of a move most traders aren’t anticipating — a breakout above $600 in the next 39 days.

SPY Trade: Positive Outcome

Let’s fast forward 39 days to expiration. Markets cooled off. SPY stayed range-bound and never made a real push higher. The ETF closed at $580 — safely below our strike.

How did our short call do? Let’s find out:

- Expiration: 39 days → 0

- Strike Price: $600

- Stock Price: $573.87 → $580 📉

- Option Price: $2.28 → $0 📉

- Breakeven Price: $602.28 (unchanged)

We kept the full premium — a $228 profit. The call expired worthless, and the margin requirement is released.

SPY Trade: Negative Outcome

Let’s fast forward 39 days to expiration. The market ripped higher after a blowout jobs report. SPY closed at $615 on the expiration of our option — well above our strike.

How did our short call do? Not great:

- Expiration: 39 days → 0

- Strike Price: $600

- Stock Price: $573.87 → $615 📈

- Option Price: $2.28 → $15 📈

- Breakeven Price: $602.28 (unchanged)

We sold the call for $2.28, but it’s worth $15 at expiration, so we lost $1,272 on the trade (15 - 2.28). That’s the risk with naked uncovered calls: limited reward, unlimited downside.

Short Call: Margin Requirements

Selling naked options comes with extremely high margin requirements. Since you’re taking on theoretically unlimited risk, your broker must protect themselves if the trade moves against you.

The margin requirement for an uncovered call is typically based on the higher value of the following two calculations, multiplied by the number of contracts and the contract multiplier (usually 100):

- 20% of the underlying price, minus the out of the money amount, plus the option premium

- 10% of the underlying price, plus the option premium

Let’s return to our earlier ABC trade to determine which margin requirement may be used here. Here are our trade details:

- Stock Price: $90

- Strike Price: $95

- Premium Collected: $0.75

Formula 1 Margin Requirement

20% of the underlying price, minus the out-of-the-money amount, plus the option premium

- 20% × $90 = $18

- Out-of-the-money amount = $95 – $90 = $5

- Premium collected = $0.75

$18 – $5 + $0.75 = $13.75 per share → $1,375 per contract

Formula 2 Margin Requirement

10% of the underlying price, plus the option premium

- 10% × $90 = $9

- Premium collected = $0.75

$9 + $0.75 = $9.75 per share → $975 per contract

Final Margin Requirement

Since brokers use the higher number, our margin requirement would be:

→ $1,375 per contract

Strike Price and Expiration Selection

To choose the right strike price and expiration cycle for your short call, you’ve got to ask yourself two simple questions:

- How market neutral or bearish am I?

- How quickly do I think the move (or lack thereof) will play out?

If your outlook is more neutral than bearish, you may benefit from choosing a strike price that’s further out of the money. You’ll collect less premium but have a higher probability of success.

If you're leaning more bearish, you might choose a strike price closer to being at the money. You’ll take in more premium but also increase your option assignment chances.

As for expiration:

- A shorter duration means quicker time decay, but less room for error.

- A longer duration gives the trade more breathing room, but premium decays more slowly.

Here’s an example of the call options I’d focus on when analyzing an options chain on VanEck Semiconductor ETF (SMH).

.png)

Short Call Risks

The two main risks of short calls are the obvious: unlimited max loss and assignment risk. Calls in the money are always at risk of being assigned, and that risk goes up the deeper in the money they are—especially as expiration approaches.

Another risk to watch for is dividend risk. If your short call is in the money and the underlying is approaching its ex-dividend date, the call buyer will likely choose to exercise early to collect the dividend. That leaves you short the stock and on the hook for paying it.

Opportunity Cost Risk

Lastly, there’s opportunity cost—a quieter but still important risk factor. Since short calls come with enormous margin requirements, you have to ask: what else could you be doing with that capital?

For example, if you sell a LEAP call for $1 ($100 max profit) and the trade ties up $2,000 in margin for a year, wouldn’t it make more sense just to park that money in Treasuries and earn a similar return—without taking on unlimited risk? Yes!

Short Calls and Implied Volatility

If you’ve ever spent much time around options traders, you’ll quickly learn that the words “implied volatility” are a core part of their vocabulary. True options traders don’t care about charts, technical indicators, or even fundamentals. What they care about—more than anything—is implied volatility.

When I was twenty-two (and fresh off my first big out trade), I showed the guy who ran the desk a chart of the stock I was now—inadvertently—short calls on. He looked at me like I was crazy, then pointed to the IV on the options chain instead.

If you’re new to IV, consider it a tide that lifts all ships—both calls and puts. When implied volatility rises, the prices of all options go up, regardless of direction. That’s because a higher IV means the market expects more significant moves, which means more value for options across the board.

For short call sellers, this means you can collect more premium from the options you sell, which may result in more profit. This is assuming, of course, that volatility falls.

Implied Volatility Example

Let’s compare two stocks trading at the same price ($100/share) with dramatically different implied volatilities:

.png)

ABC and XYZ stocks are trading at the same $100 per share price, but their option prices differ dramatically due to their IV levels (15% vs 45%).

For the same strike prices:

- ABC's options (low IV at 15%) are much cheaper across all strikes

- XYZ's options (high IV at 45%) command significantly higher premiums

For example, at the $100 strike (at-the-money):

- ABC: bid/ask of $1.45/$1.50

- XYZ: bid/ask of $3.75/$3.85

This shows why selling calls in high IV environments is potentially more profitable. When you sell a call option on XYZ with 45% IV, you collect much more premium than selling the same option on ABC with only 15% IV.

The market is pricing in the expectation that XYZ will make much bigger future moves than ABC, which translates directly to higher option values across all strikes.

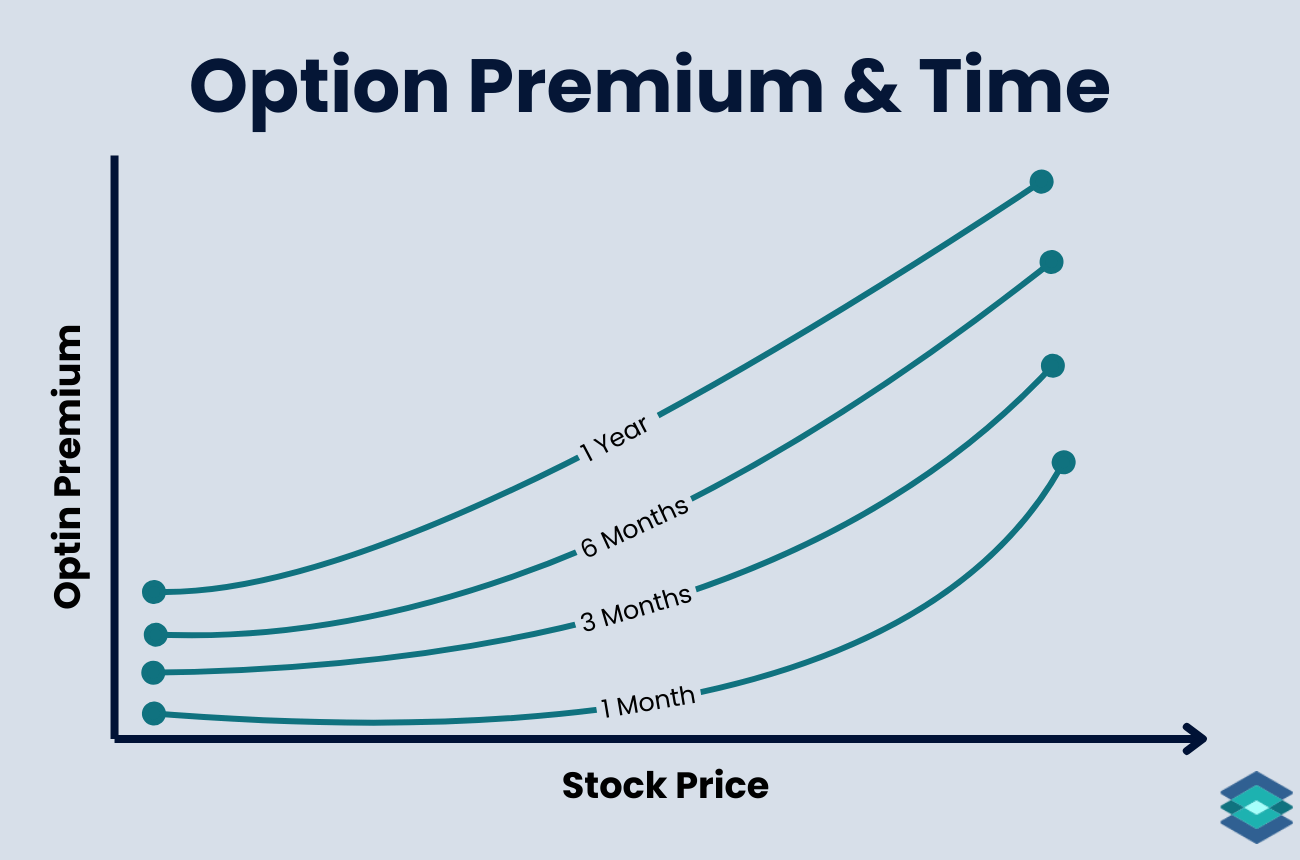

Short Calls and Time Decay

Short call options benefit from time decay, or ‘theta.’

With the passage of time, assuming all else stays the same—like price and IV—options contracts lose value. This time decay really starts to speed up as expiration gets closer, accelerating noticeably around 45 days to expiration (DTE).

.png)

Therefore, sellers of options may want to choose expiration dates at or near this 45 DTE mark. When you sell options like LEAPs with a long time until expiration, you'll be waiting a while for time decay to pick up while at the same time tying up a lot of cash in margin, which could otherwise earn a nice return at the risk-free rate.

Short Calls and The Greeks

In options trading, the Greeks are a series of risk management tools that hint at the future price of an option based on changes in different variables. Here are the 5 most important Greeks to know:

- Delta – Measures how much the option price moves relative to the underlying stock.

- Gamma – Tracks how Delta changes as the stock moves.

- Theta – Measures time decay, showing how much value the option loses daily.

- Vega – Sensitivity to implied volatility, affecting option price.

- Rho – Measures impact of interest rate changes on the option price.

And here is the relationship between short calls and these Greeks:

Managing a Short Call

As I’ve said, trading options—especially naked ones—isn’t passive investing. You’ve got to stay on top of your position, constantly monitoring it to mitigate risk and maximize profit potential.

Closing a Short Call

When you sell a call option, you're not obligated to hold it until expiration. In fact, the vast majority of options trader exit their positions before expiration. If your short call has lost significant value—say 90% of its initial premium—consider buying it back to close the position.

Doing this frees up your margin and completely eliminates early assignment risk. The last bit of premium is often the hardest to capture and carries the most risk relative to reward anyway.

Rolling a Short Call

If your short call is moving against you, consider rolling the position. Rolling involves closing your current short call while simultaneously opening a new one with either a higher strike price, a later expiration date, or both.

When you roll up (to a higher strike), you reduce your assignment risk by moving your strike further out of the money. This usually costs money, as you're buying back an option with intrinsic value and selling one with less value. This trade is called a vertical spread.

When you roll your option to a later expiration, you're giving yourself more time for the stock to move back down potentially. This typically brings in additional premium, which might offset or exceed the cost of closing your current position. This trade is called a calendar spread.

The ideal roll—up and out—gives you both a higher strike price and more time, potentially for a credit. This maintains your positive theta position while reducing immediate assignment risk.

Short Call Calculator

Use our short call calculator below to explore how different market outcomes affect your potential profit or loss.

⚠️Selling a call option involves unlimited risk if the underlying stock rises sharply. This strategy is not suitable for all investors and should only be used with a full understanding of the risks. Besides the initial credit received, commissions and fees are not included in above examples and may significantly impact trade outcomes. Read The Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options before trading options.

FAQ

A naked call option is when you sell a call on an underlying asset without hedging it with stock or other options. It’s a high-risk trade with unlimited loss potential if the stock takes off.

An example of an uncovered call would be selling a 105 strike call on a stock trading at $100, without owning the stock. If the stock jumps to $120, your loss is the difference—minus the premium collected.

The two most significant risks with uncovered calls are unlimited loss potential and early assignment. If the call goes deep in the money, you could be assigned and forced to deliver shares at a loss.

The riskiest options strategy is the naked (uncovered) call because the potential loss is unlimited. There’s no cap on how high a stock can go—and that’s what makes it dangerous.

A short call is a bearish to market-neutral trade. You want the stock to stay below the strike price so the option expires worthless.

You can exit a short option position by letting it expire worthless, closing it early by buying it back, or rolling it to a later date or higher strike using a vertical or calendar spread.

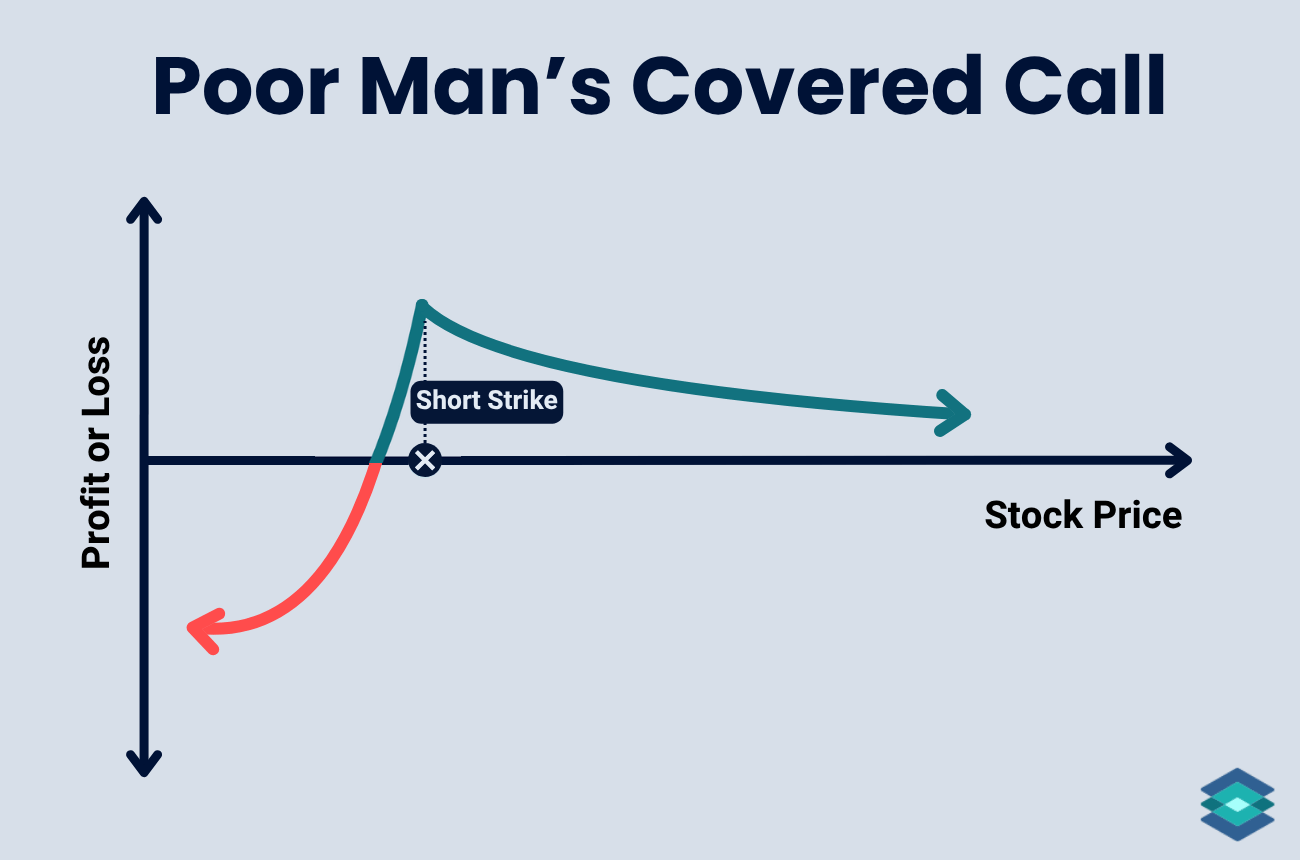

A covered call is when you sell a call option against 100 shares of stock you already own. Because you hold the shares, your max profit is the premium collected plus any gains up to the strike. Your max loss is the same as owning the stock outright minus the premium collected and occurs if the stock falls to $0.