Option Moneyness Guide: ITM vs ATM vs OTM

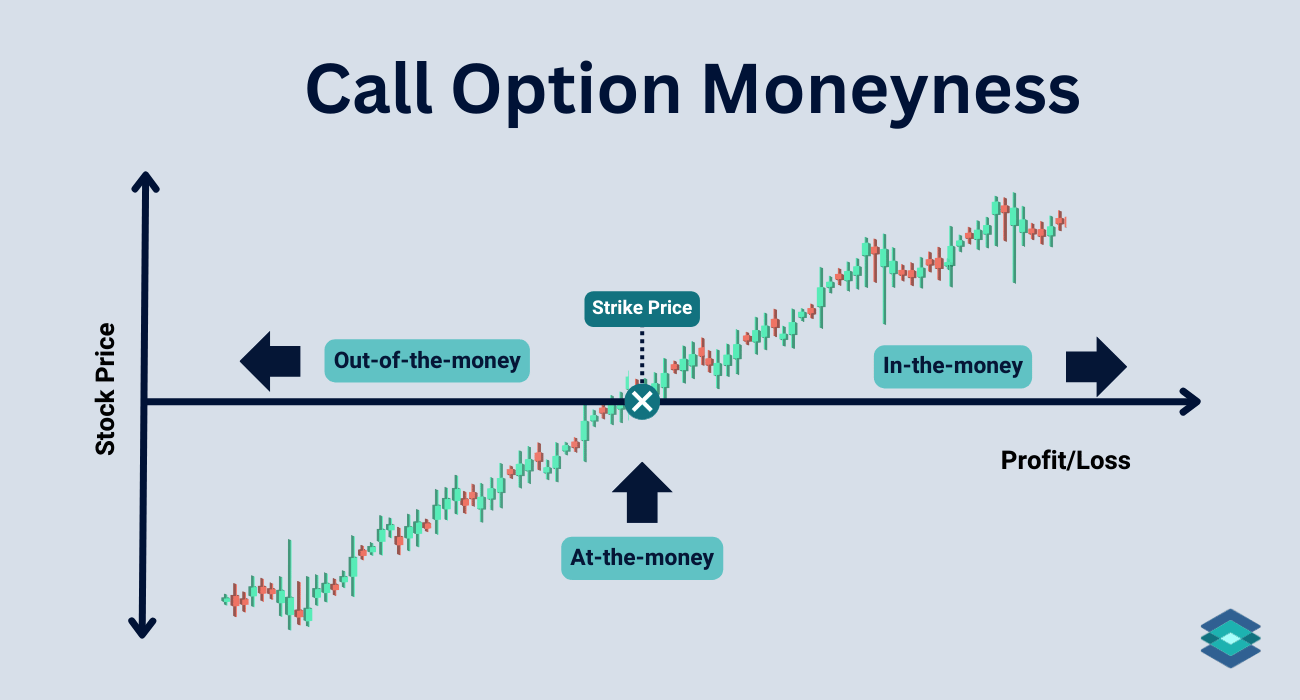

In options trading, moneyness refers to the relationship between an options contract's strike price and the underlying asset's current price. All options fall into one of three moneyness states: in-the-money (ITM), out-of-the-money (OTM), or at-the-money (ATM).

To be a successful options trader, you must understand option moneyness, which is the relationship between the price of the underlying asset, like a stock, and the strike price of an options contract.

In this guide, we’ll break down how to calculate moneyness, explain how it’s used to price options and show you how understanding moneyness can help you mitigate unnecessary risks.

Highlights

- Moneyness refers to how an option’s strike price compares to the underlying asset’s current market price - whether it's in-the-money (ITM), at-the-money (ATM), or out-of-the-money (OTM).

- Calculating Moneyness: A call is ITM if the market price is above the strike, while a put is ITM if the market price is below the strike.

- Exercise Risk: ITM options are exercised frequently, creating risk for option sellers needing to cover stock, while OTM options expire without being exercised.

What is Moneyness in Options Trading?

An options contract will always fall into one of three moneyness states. Being informed about which state an option is in tells you whether an option has any intrinsic value and is worth exercising. Moneyness also helps sellers determine whether they’re at risk of being assigned.

Moneyness is pretty straightforward. If you own a call option with a strike price of 100 and the stock’s trading at 102 on expiration, your option has $2 of value. You could exercise the call, buy the stock at your strike price of 100, and then sell the stock at 102. Your option, therefore, is in-the-money by $2.

Before moving on, let’s break down the key moneyness terms and their respective abbreviations.

In-the-money (ITM)

- Call Option: When the market price of the underlying asset is above the strike price.

- Put Option: When the market price of the underlying asset is below the strike price.

Out of the Money (OTM):

- Call Option: When the market price of the underlying asset is below the strike price.

- Put Option: When the market price of the underlying asset is above the strike price.

At the Money (ATM):

- When the market price of the underlying asset equals the strike price for both call and put options.

American vs. European Style Options

.png)

There are two varieties of options contracts: American-style and European-style.

In this article, we’ll focus on American-style options, which allow the owner to exercise their option any time before expiration. Most U.S. stocks and ETFs (exchange-traded funds) fall under this category.

European-style options, on the other hand, can only be exercised at expiration. These are commonly used for popular index options like SPX and NDX. European-style options are cash-settled, meaning no underlying position is physically exchanged. This is because European-style options like SPX and NDX typically don’t offer tradable underlying securities.

Calls vs. Puts: Option Moneyness

Here’s a quick refresher on American-style call and put options. 👇

- A call option gives the owner the right, but not the obligation, to purchase the underlying asset (e.g., stock) at the strike price on or before expiration.

- A put option gives the owner the right, but not the obligation, to sell the underlying asset at the strike price on or before expiration.

Calls and puts have an inverse relationship when it comes to moneyness. The visual below illustrates how a call and put option moves from out-of-the-money to in-the-money with varying underlying asset prices.

Moneyness Calculations

As I mentioned before, determining moneyness becomes intuitive over time. However, there are also mathematical equations that can tell you whether an option is ITM or OTM and to what degree.

Call Options Moneyness Calculation:

Moneyness = Market Price of Underlying Asset−Strike Price

If the result is positive, the call option is in-the-money (ITM). If it's negative, the call option is out-of-the-money (OTM).

Put Options Moneyness Calculation:

Moneyness = Strike Price − Market Price of Underlying Asset

If the result is positive, the put option is in-the-money (ITM). If it's negative, the put option is out-of-the-money (OTM).

Moneyness: Intrinsic & Extrinsic Value

The most helpful aspect of an option's moneyness is that it tells us how much intrinsic value an option has - or, in other words, how deep in-the-money an option is.

However, intrinsic value is only part of an option's total value. The remaining portion is extrinsic value, which accounts for factors like time and implied volatility.

Once we know an option's intrinsic value, calculating its extrinsic value is easy. For example, if an option costs $3 and is in-the-money by $2, its extrinsic value is $1.

Extrinsic Value = Option Premium (Market Price) − Intrinsic Value

What’s important to understand is that as time passes, extrinsic value decays. This mean the options premium falls. By expiration, there is no extrinsic value left (since there’s no time left), so the option's worth is 100% intrinsic value.

.png)

On the other hand, if the option is out-of-the-money at expiration, it expires with neither intrinsic nor extrinsic value. In options, we call this ‘expiring worthless.’

⚠️ Besides the initial debit paid, it is essential to consider the commissions and fees associated with most options transactions when calculating the net profit or loss. These fees can significantly impact the overall return on investment.

📖 Options Trading: Liquidity Guide

Option Moneyness and Delta

In options trading, delta is a very useful tool. This option ‘Greek’ tells us how much an option’s price is expected to change based on a $1 move in the underlying asset. Here's our video on the subject👇

For example, if you own a call option with a delta of 0.6, the option’s price is expected to increase by $0.60 for every $1.00 increase in the underlying asset's price.

Delta changes as an option moves from out-of-the-money (OTM) to at-the-money (ATM) to in-the-money (ITM). The delta range spans from 0 to 1 for calls and from 0 to -1 for puts.

When a call option’s delta is close to 1 (or close to -1 for puts), it means the option moves almost dollar-for-dollar with the underlying asset. This happens when the option is deep in-the-money (ITM).

Conversely, when the delta is near zero, the option barely moves with changes in the asset’s price. These deltas typically indicate out-of-the-money (OTM) options.

As you probably guessed, at-the-money options tend to have deltas around 0.50.

Example Deltas with Stock at $100

Moneyness: Exercise and Assignment

Long call and long put options are typically only exercised when they are in-the-money, as this allows the holder to immediately profit by buying (for calls) or selling (for puts) the underlying asset at a better price than the current market price. Exercising out-of-the-money options is rare because doing so would result in an immediate loss.

In-the-money American-style options pose a risk for options sellers (also known as writers), especially as the option moves deeper into the money.

Deep-in-the-money options are mostly comprised of intrinsic value, which makes holding the option less attractive since it tracks the price of the underlying stock. In these cases, holders frequently choose to exercise their option.

.png)

When assigned, option sellers are required to deliver the stock, typically 100 shares per contract for both calls and puts. If the seller doesn’t have the necessary funds to cover the stock, their account may be liquidated to meet a margin call.

Moneyness and Dividend Risk

Options are derivatives, which means they don't have the same rights as equity holders, such as the right to receive dividends. If you’re long a call option that is in-the-money around the ex-dividend date, it may make sense to exercise your option before the ex-dividend date to convert it to stock and capture the dividend.

This creates a significant risk for option sellers. Those who are short in-the-money and at-the-money call options near the ex-dividend date need to take precautionary measures to avoid being assigned at an unfavorable price, especially when the option is deep in-the-money. Usually, the best action to take is to close all short option positions at risk.

I’ve seen many traders take big losses by not paying attention to dividend dates, which can result in assignments at an unnecessary cost.

Moneyness and The Options Chain

On an options chain, moneyness is often indicated by a shaded region. Option chains also display the delta, as mentioned earlier.

Below is an options chain from the TradingBlock platform for SPY (SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust) options expiring in one week. Notice how the shaded regions converge at the 585 strike price, representing the at-the-money options.

Explore Options Trading With Virtual Trading

With TradingBlock’s Virtual Trading platform, you can trade options in a simulated environment. Check it out below today!

FAQ

In options trading, moneyness refers to the relationship between the price of the underlying and the strike price of an option. It also informs inventors of how much intrinsic value an option has.

To calculate the moneyness of a call option, subtract the strike price from the current market price of the underlying asset.

Option moneyness represents an option's intrinsic value, and since intrinsic value can't be negative, moneyness can't be negative either. A call or put option is either in-the-money (with positive intrinsic value) or out-of-the-money (with zero intrinsic value).

If you’re long an option, in-the-money (ITM) is generally better because it means the option has intrinsic value. You may profit by exercising it or selling it in the open market. On the flip side, if you’re short an option, you want it to stay out-of-the-money (OTM), so it expires worthless, allowing you to collect the entire premium.

A call option is in the money when the price of the underlying asset is above the strike price. For puts, the option is in the money when the underlying price is below the strike price.

It depends on your market outlook. Out-of-the-money options are cheaper but come with a lower probability of success. In-the-money options are more expensive but offer a higher probability of success.

Let’s say a stock is trading at $100. If you have a call option with a 95 strike, it’s in-the-money since the underlying is above the strike, giving it intrinsic value of $5. On the other hand, a call with a 105 strike price is out-of-the-money with the stock at $100 because the stock price hasn’t reached the strike, meaning it has no intrinsic value yet.

When options are out of the money, they don’t have any intrinsic value. For a call option, this happens when the strike price is above the market price of the underlying asset. For a put option, it’s OTM when the strike price is below the market price.

.png)

.avif)