Long Straddle Options Strategy: Beginner's Guide

The long straddle is a low-probability, net debit options trade that involves buying both a call and a put option at the same strike price. The trade profits when implied volatility rises or when the underlying makes a big move, up or down.

The long straddle is a costly options trade where you buy a call and a put at the same strike price and expiration, aiming to profit when:

- Upside breakeven: stock rises above strike + total premium

- Downside breakeven: stock falls below strike – total premium

This low probability trade can also profit if only implied volatility rises and price stays the same.

Highlights

- Risk: Limited to the total premium paid, but high: you need a big move just to breakeven.

- Reward: Unlimited on the upside; substantial on the downside. Big moves in either direction are your friend.

- Outlook: Volatile - you want IV to rise and the price to move a lot.

- Edge: Long straddles can benefit from sudden volatility spikes or major price shocks.

- Time Decay: Unfavorable — theta works against you every day the stock sits still or changes little.

- Approximate Profitability: Very low

Long Straddle: Trade Components

Here’s how you construct a long straddle:

- Buy 1 call option

- Buy 1 put option (same strike)

- Both options have the same expiration date

- Generally, both options are at the money (not always)

This creates a net debit position with no directional bias. You're paying premium on both sides, betting the underlying makes a big move away from the strike price before option expiration.

Ideally, straddles are put on in one trade. If you leg in, you’re exposed to directional risk.

Here’s how to set up a long straddle on the TradingBlock dashboard:

Market Outlook: When to Buy a Straddle

Here are a few scenarios where it may make sense to buy a straddle:

- Uncertain Direction: You expect a big move, but don’t know which way. Examples are events like earnings, Fed announcements, or major product launches.

- Low Implied Volatility (IV): The best time to buy options is when they’re cheap. If IV is low and you expect it to rise, a long straddle can benefit from both the move and volatility expansion.

- Hedging: Straddles are a great, although very expensive, way to hedge against extreme moves or IV hikes. An example would include managing a delta neutral portfolio.

Long Straddle Payoff Profile

And now let’s break down the maximum loss, breakeven points, and profit potential for this trade.

Maximum Profit Zone

Since the long straddle involves a long call, the max profit on the call side of the trade is theoretically infinite. The max profit potential on the put side is significant, as the underlying asset (stock, index, ETF, etc.) can go to zero.

For example, let’s say you pay $5 total for a straddle on ABC, a high-beta tech stock trading at $100:

- Buy 100 strike call for $2.50

- Buy 100 strike put for $2.50

- Total debit (max loss) = $5.00

Now let’s say ABC gets acquired during the life of the straddle and the stock soars 25%, jumping from $100 to $125. Here’s what happened to our options:

- The 100 call is now worth $25 (intrinsic value = $125 – $100)

- The 100 put expires worthless

- Net value of position = $25

- Profit = $25 – $5 = $20

Big move, big payout. That's exactly what a long straddle is built for. It’s also important to keep in mind that you don’t only need a huge price move for a straddle to profit. When implied volatility jumps (which reflects the market’s expectations for future movement), the price of both options can rise, even if the stock hasn’t moved much yet.

Maximum Loss Zone

Whenever you are in a net debit options trade (like this one) the most you can lose is the premium paid. Therefore:

Max Loss = Total Premium Paid

Incurring a max loss on a long straddle is rare as the underlying asset would have to close on expiration day exactly at the strike price. You'll likely preserve some premium, but it's worth mentioning that over time long straddles tend to lose money.

For example, let’s say we buy both the 100 strike call and the 100 strike put on ABC for a combined debit of $5.00:

- Buy the 100 call for $2.50

- Buy the 100 put for $2.50

- Total premium paid: $5.00 ($500)

If ABC closes between directly at our strike price, both options will expire worthless. Again, very unlikely.

Breakeven Zone

A long straddle has two breakeven points: one on the upside, one on the downside. Here’s how to calculate them:

Upper breakeven = Strike Price + Total Premium Paid

Lower breakeven = Strike Price – Total Premium Paid

In our previous example, we paid a total of $5.00 for the 100 strike call and 100 strike put on ABC. This would leave us with breakevens of:

- Upper breakeven = 100 + 5 = 105

- Lower breakeven = 100 – 5 = 95

We can see these breakeven zones below:

Margin Requirements

Because we can lose no more than the debit paid for a long straddle, this is also the margin required for the trade. For example, if the net debit of our trade is $3, our total trade cost is $300.

But just because our max loss is capped up front doesn't make the trade less dangerous. Always consider how much movement (or volatility) you realistically expect before placing this trade.

Long Straddle: Moneyness and Skew

Most long straddles are bought at the money, meaning the strike price matches the stock’s current price. You can, however, buy straddles at different levels of moneyness if you have a directional bias.

For example, if ABC is trading at $100 and you think it’s headed higher, you might buy the 105 straddle instead. It’s still a long straddle, same strike call and put, but now it has a bullish tilt.

This is called “skewing the straddle.” The trade becomes more directional, and your breakeven points shift accordingly.

Examples:

- Bullish skew: Buy the 105 straddle when the stock is at 100

- Bearish skew: Buy the 95 straddle when the stock is at 100

Long Straddle: SMH Trade Example

The market has been in a lull lately. I am expecting volatility to increase, particularly in semiconductor stocks as earnings are coming up in a few weeks.

Over the next 30 days or so, I think semiconductors could break out in either direction. To take advantage of that potential, I'm buying an at the money straddle on the VanEck Semiconductor ETF (SMH). Here’s why I like SMH:

- Broad semiconductor exposure

- Tight bid/ask spreads and good options volume

- Plenty of strike and expiration choices

Let’s jump over to the TradingBlock dashboard and find an expiration and strike price that gives us enough time to catch the move.

SMH Trade Setup

Notice on the above options chain how high the premiums are for these contracts. At the money options are always priced higher than out of the money ones, and with volatility elevated, those prices get even richer. The bid/ask spreads can be wide too, especially when implied volatility is pumped up like this.

That’s why it’s crucial to use limit orders when trading options. Always start at the midpoint. If you don’t get filled right away (and want to), walk your order up in penny or nickel increments until you do. And if you can’t get a decent fill, skip the trade. You can learn more about options trading liquidity metrics here.

We’ll assume we got filled at the midpoint on this one, which means we paid a total debit of 20.47. You can see this below:

Trade Details

And here are the details of the trade we just put on:

- SMH Price: 212.30

- Expiration: 35 days

- Buy 212.5 Call @ $10.65

- Buy 212.5 Put @ $9.82

- Net Debit Paid: $20.47 ($2,047 total)

- Breakeven Prices: 212.50 ± 20.47 = $192.03 / $232.97

- Max Loss: $20.47 ($2,047 total)

- Max Profit: Unlimited

- No Margin Requirement (just premium paid)

The most we can lose here is the $20.47 ($2,047) we paid in premium. We need SMH to move outside of $192.03 or $232.97 to turn a profit. The further it moves, the more we may make.

Let’s explore a few trade outcomes!

Long SMH Straddle: Losing Outcome

Thirty-five days have passed, and expiration is upon us. After all that time, SMH drifted back to $212 a share, just shy of our strike, and the volatility we were hoping for never came.

The 212.5 call expired worthless, and the 212.5 put finished just $0.50 in the money, returning us a meager $50 on a $2,047 trade.

Here’s where we ended:

- SMH Price: $212.30 → $212.00 ⬇️

- Expiration: 35 days → 0

- Buy 212.5 Call @ $10.65 → $0.00

- Buy 212.5 Put @ $9.82 → $0.50

- Final Value: $0.50 on the put

- Net Loss: $20.47 – $0.50 = $19.97 ($1,997 total)

- Percent of Premium Lost: 97.6%

Long straddles are binary bets. You either catch a big move or you get nothing. This time, we got nothing, which over the long run seems to be a theme with long straddles.

Here’s how our trade performed over time:

.png)

Long SMH Straddle: Winning Outcome

In this outcome, we got the breakout we needed. It took awhile, but that volatility finally arrived and sent our put soaring:

Here’s where the trade finished:

- SMH Price: $212.30 → $180.00 ⬇️

- Expiration: 35 days → 0

- Buy 212.5 Call @ $10.65 → $0.00 ❌

- Buy 212.5 Put @ $9.82 → $32.50 ✅

- Final Value: $32.50 put value

- Net Profit: $32.50 – $20.47 = +$12.03 per share → +$1,203 total

At expiration, an option’s value is 100% intrinsic value, meaning it’s entirely based on how far in (or out) of the money it is. Since SMH closed at 180, our long put finishes with a value of 212.5 minus 180, giving us $32.50. Extrinsic value, which accounts for time, is gone from the equation.

Choosing Your Deltas

In options trading, delta tells you two things:

- How much an option moves for every $1 move in the stock

- The probability the option expires in the money

We’re going to focus on the second one here.

Since at the money options have around a 50% chance of finishing in the money, their deltas are usually right around 0.50, or “fifty,” as we say in the biz.

When I’m putting on a long straddle, I’m looking for that sweet spot right at or near the money. But stocks don’t always land perfectly on strike, so I usually give myself some wiggle room, anywhere from 0.45 to 0.55 delta works.

If the put is trading at 0.52 delta, the call will be a bit under, and vice versa. That’s normal. You’re still centered, which is key with long straddles.

Also worth noting is at the money options are more sensitive to price movement. That higher gamma cuts both ways: if you catch the move early, great. If not, time decay starts chipping away fast.

Long Straddles and Time Decay

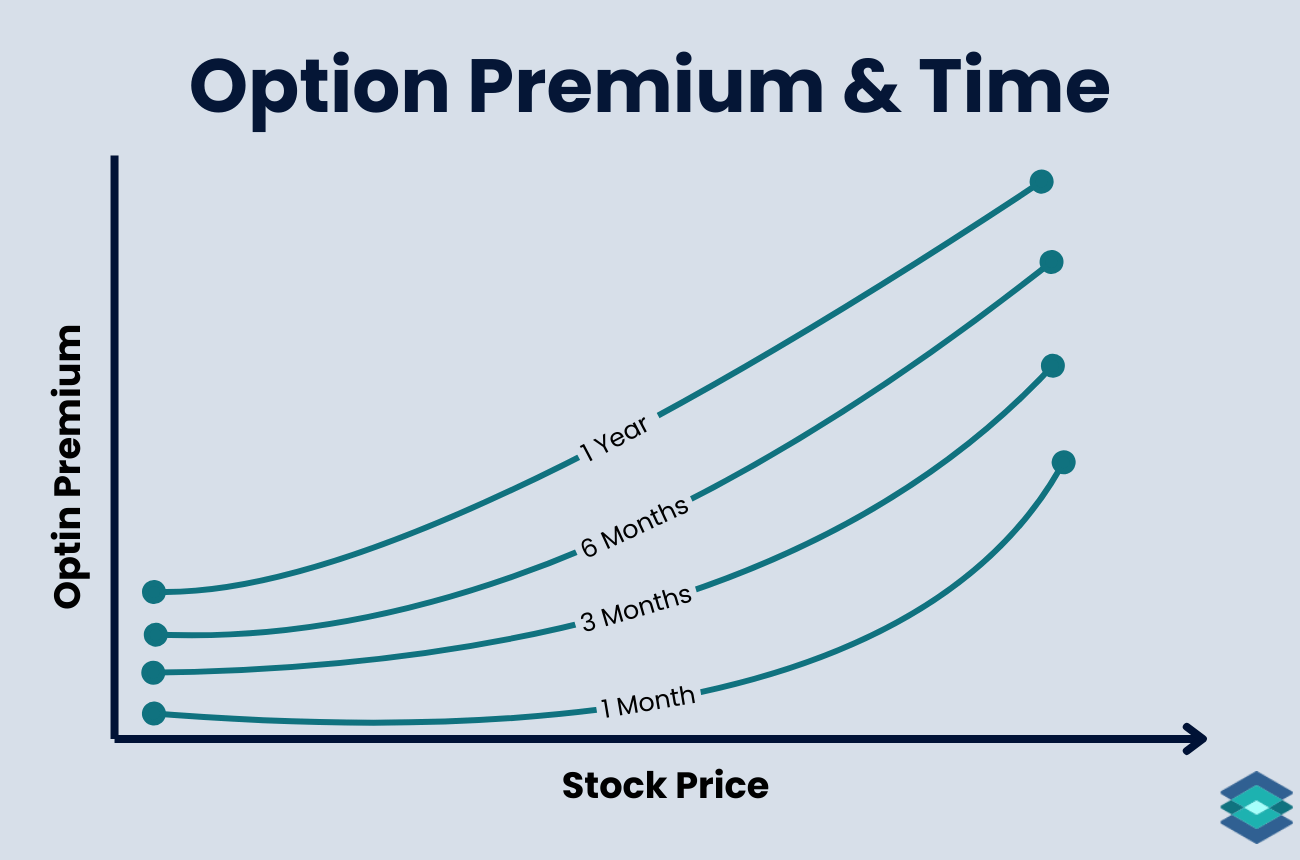

By far and wide, professional traders prefer selling options over buying them. This is because, in a constant environment, options perpetually shed value. And the closer expiration gets, the faster that decay picks up. We can see this below:

.png)

So, do we want to buy options before they enter the red zone (~45 days)?

Not necessarily. While it’s true that time decay picks up the closer you get to expiration, buying options earlier just means paying more in extrinsic value (comprised of time and implied volatility).

Personally, I like buying options within the 30-45 days to expiration window, and I almost always close before expiration. 50% over the initial premium is more than sufficient for myself.

Also, don’t forget you want time to adjust or manage the trade if things don’t go your way. If you buy a straddle with 2 DTE and the stock doesn’t move after day one, there’s not going to be much premium left to work with to readjust. Buying options on 0DTE is more akin to gambling than trading.

Theta Selection

Theta is the option Greek that tells us how much value an option will shed over one day. Therefore, since we’re long options, theta is our enemy. We want to buy options with low theta.

Generally speaking, I look to buy thetas under 0.20 (combining the call and put), but this is highly contingent upon the trade and market conditions.

For example, the trade war is in full swing right now, and you can’t even buy a 30-day straddle on an S&P 500 ETF for under 0.45 net theta.

Implied Volatility and Straddles

.png)

When you buy a straddle, you’re betting on two things:

- A significant price move

- A rise in implied volatility

If you only get one, the trade probably won’t be profitable. Even if you get a nice move, a drop in IV can wipe out your gains.

You generally want to buy straddles when IV is low and expected to rise. So, how do you know if IV is low for a specific underlying asset?

- IV Rank – Tells you where current IV sits compared to the past year (0–100%). Low rank = cheap options.

- IV Percentile – Tells you what percent of days over the past year had lower IV. Higher percentile = higher current IV.

Long Straddle vs Short Straddle

.png)

The long straddle is a long volatility bet: you’re hoping for a big move in either direction. A short straddle is the opposite, profiting with little price movement.

- Long straddle: Buy a call and put at the same strike. High risk, unlimited upside, but you need a big move to win.

- Short straddle: Sell a call and put at the same strike. High reward, unlimited risk.

Long Straddle vs Long Strangle

The long straddle and long strangle are very similar option strategies, with one huge difference: the straddle involves buying a call and put option at the same strike price. In contrast, the strangle involves buying a call and put option at different strike prices.

Strangles are better when you expect a larger move than a straddle requires, but still want some margin for error.

Here’s a table comparing the two option strategies.

Managing a Long Straddle

Since long options have no early assignment risk, the long straddle likely requires less active management than short option positions. However, you still need to keep an eye on a few things:

Take Profits on the Move

If you catch a big move and the straddle is up 25–50%, don’t get greedy. Straddles lose value fast once things calm down, so it's smart to lock in profits while the market's still moving.

Cut the Trade if Nothing’s Happening

If the stock stagnates and IV drops, your straddle will begin decaying in value rapidly. If nothing’s happening and you're losing premium daily, it may be better to cut your losses or adjust your strike price/expiration.

Use IV as a Guide

Straddles thrive on movement and rising implied volatility. If IV spikes after you enter the trade, consider exiting, even if the stock hasn’t moved much yet. You can sometimes make money just on the vol pop.

You Don’t Have to Hold to Expiration

Most of the time, you’ll want to close early to either take profits or limit losses. Holding to expiration is very risky.

Watch liquidity

I’ve never placed an options trade without using a limit order. In addition to limit orders, it’s important to run through this liquidity checklist:

- Is there adequate size?

- Is there high volume?

- What is the open interest?

- How wide are the spreads?

Long Straddles and The Greeks

In options trading, the Greeks are a series of risk tools that hint at the future price of an option based on changes in different variables. Here are the 5 most important Greeks to know:

- Delta – Measures how much the option price moves relative to the underlying stock.

- Gamma – Tracks how Delta changes as the stock moves.

- Theta – Measures time decay, showing how much value the option loses daily.

- Vega – Sensitivity to implied volatility, affecting option price.

- Rho – Measures impact of interest rate changes on the option price.

And here is the relationship between long straddles and these Greeks:

⚠️ Long straddles are expensive, high-risk trades. While your max loss is capped at the premium paid, that premium isn’t cheap, and time decay works against you every day. This strategy isn’t for everyone. Commissions and fees are not reflected in the examples above. Always read The Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options before trading.

FAQ

The long straddle is a great strategy for investors expecting both a significant directional move in price and a rise in implied volatility (IV).

You can make money on a straddle when the underlying asset’s price rises or falls past the two breakeven points, which are the strike price plus and minus the total premium paid.

The long straddle is both bullish and bearish as it is comprised of buying both a call option and a put option.

You’d buy a long straddle if you think a big move is coming, but you don’t know which direction. It’s also a bet that IV will rise after you enter the trade.

Both are neutral, long volatility trades. A straddle buys the call and put at the same strike, while a strangle uses different strikes, making it cheaper, but requires a bigger move to win.

In options trading, a butterfly consists of three strike prices. For example, you buy one lower strike call, sell two at-the-money calls, and buy one higher strike call. All of these options have the same expiration. It’s a defined-risk, directionless trade that profits if the stock pins the middle strike at expiration.

The short straddle is a strong premium-selling strategy if you expect the stock to stay near the strike. It performs best in high-IV environments with limited expected movement. It’s high risk, but high probability.

.avif)