Calendar Spread Options Strategy: Beginner's Guide

A calendar spread is an options strategy where you buy and sell the same type of option at the same strike, but with different expirations. The goal is to profit from time decay and shifts in implied volatility. One leg is long, the other is short. Both legs are entered at the same time.

Calendar spreads are market-neutral, net debit trades that profit when the stock stays near the strike, as the short option decays faster than the long one. These spreads can also benefit from rising implied volatility on the longer-dated leg.

Highlights

- Risk: Limited to the net debit paid. The worst-case scenario is both options expire worthless if the stock moves too far from the strike.

- Reward: Profit peaks when the stock lands near the strike at front-month expiration. Gains come from short option decay and retained long value.

- Outlook: Market-neutral strategy ideal for range-bound stocks or volatility plays. Can be tilted bullish or bearish depending on strike placement.

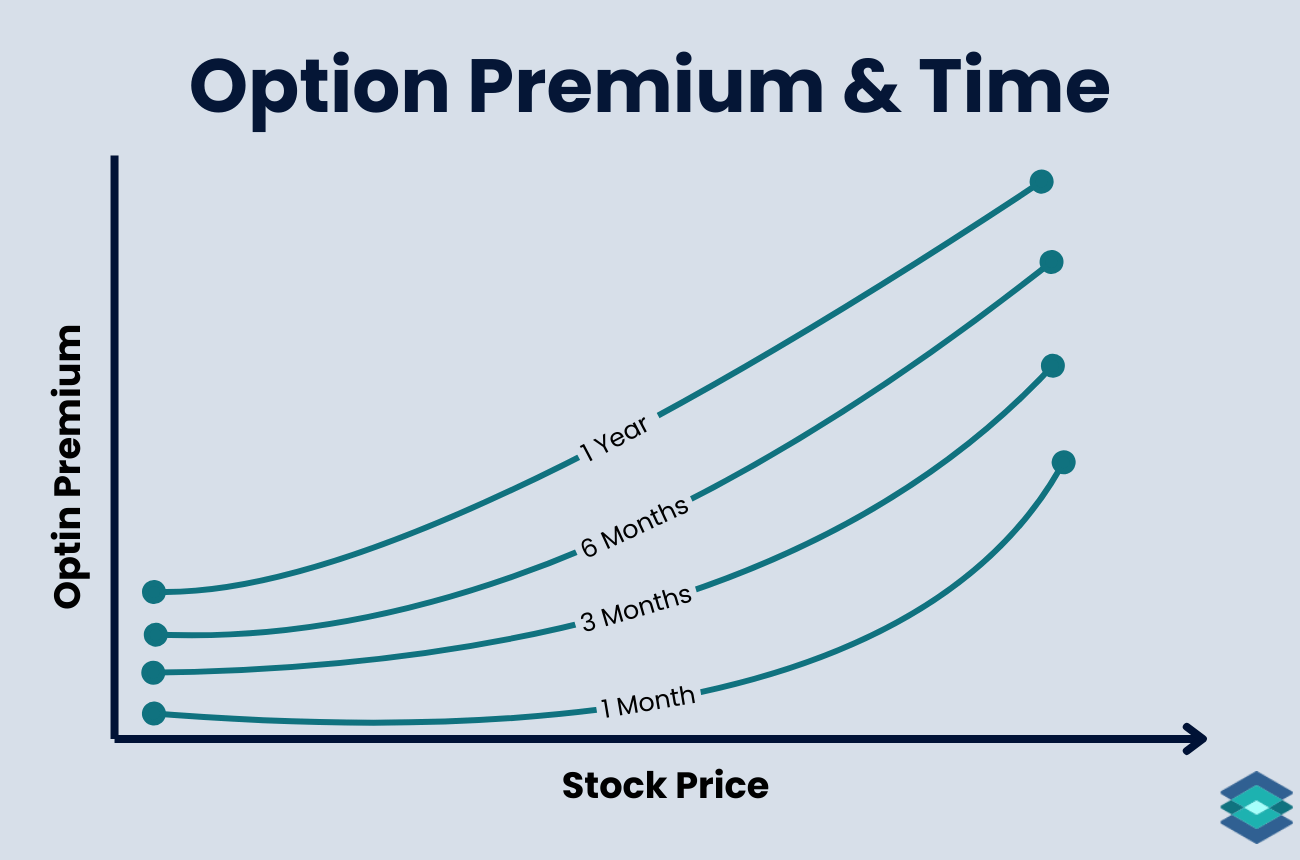

- Time Decay: Theta works in your favor as the short decays faster than the long. Decay accelerates as expiration nears.

- Volatility Edge: Rising implied volatility benefits the long leg more than it hurts the short. Best entered when IV is low with expectations for it to rise.

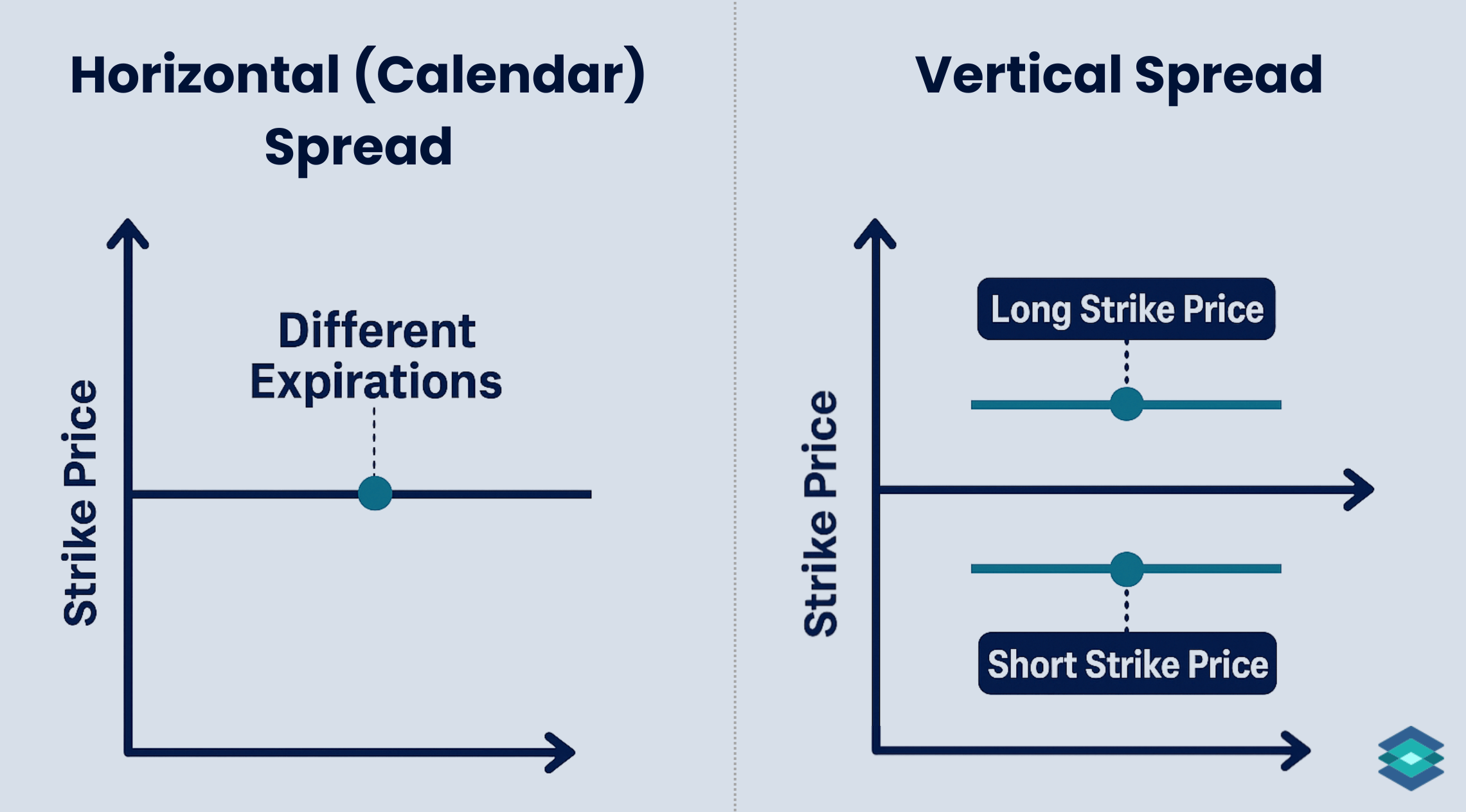

Horizontal (Calendar) vs Vertical Spread

Most people trading calendar spreads have a good idea of what a vertical spread is. In short, a vertical spread involves buying and selling at two different strike prices on the same expiration cycle. You choose the strike prices ‘vertically’ on the options chain.

Horizontal spreads use the same strike price, but different expiration months. That’s why they’re also called time spreads. Here's how the two compare visually:

When you’re dealing with multiple expiration months, it adds a layer of depth. This can make payoffs a little less straightforward, but we’ll walk through it all in this article.

Calendar Spread Components

Here’s how you build a calendar spread:

- Sell 1 near-term option (call or put)

- Buy 1 longer-term option (same type and strike)

- Both options use the same strike price

- Same underlying, different expirations

Ideally, the trade is entered in one spread. If you leg in, you’ll be exposed to directional risk. We can see a calendar spread setup for SPY (SPDR S&P 500 ETF) on the TradingBlock dashboard below:

Market Outlook: When To Trade Calendar Spreads

Calendar spreads are best used when you're neutral to slightly directional and expect the stock to stay near a specific price in the short term.

They work well when:

- You expect low volatility to rise, especially on the back-month

- The stock is range-bound or drifting slowly toward a target

- You want to capitalize on time decay without making a strong directional bet

- You're trading around events, like earnings, but want limited risk and defined exposure

Calendar Spreads and Margin Requirements

The cost of a calendar spread is the net premium paid. If the total debit is 1.20, your total cost and money at risk is $120 per spread.

Keep in mind that if you hold past short expiration, you’re left with the long option on its own, which can change your exposure and raise margin requirements.

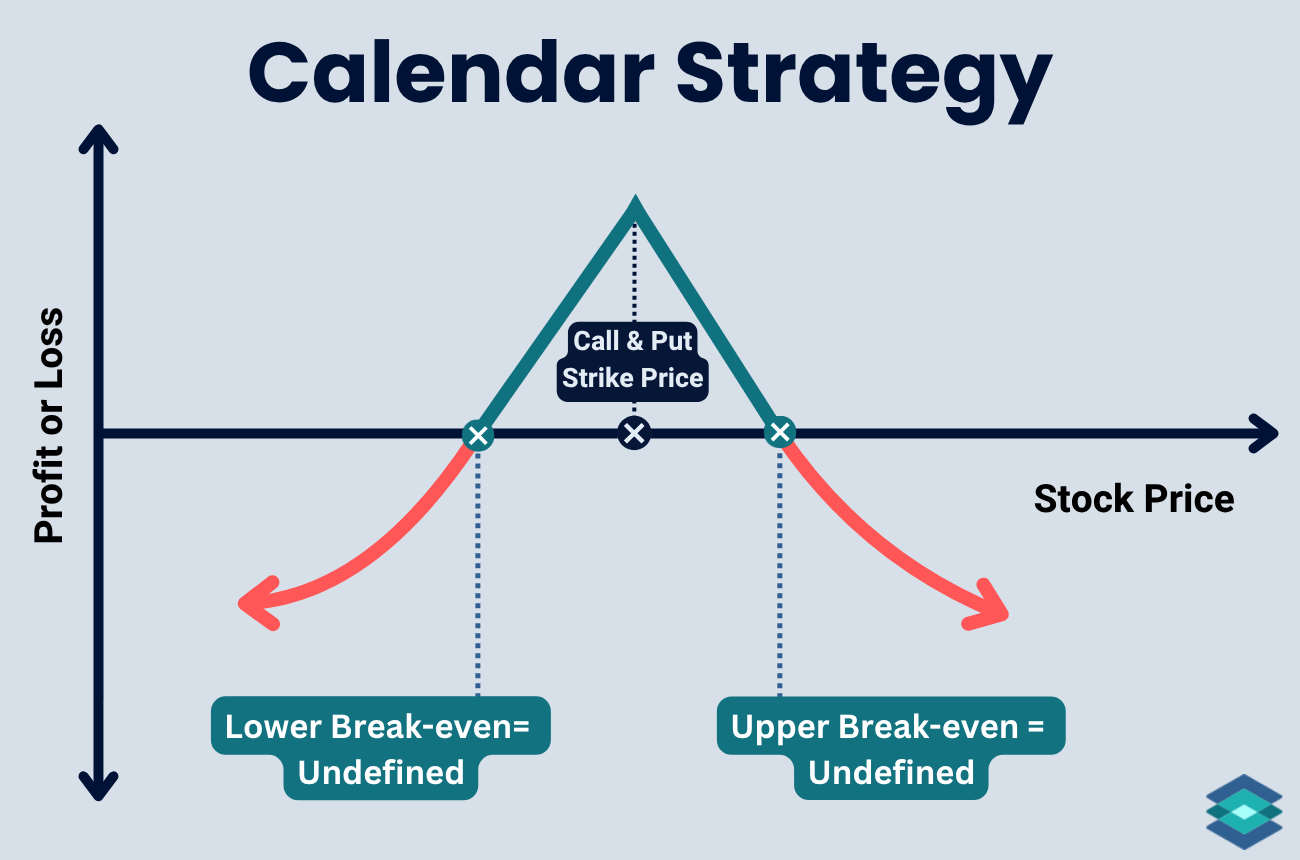

Calendar Spreads Payoff Profile

Let’s now review the maximum profit, loss, and breakeven for this trade.

Maximum Profit Zone

Max profit happens on a calendar when the stock closes right at the strike price when the short call expires. That’s where the short option expires worthless, and the long call still holds strong time value. But who’s to say what that final long call value will be?

There’s no fixed maximum profit formula on calendars like with vertical spreads. This is because the long call's value depends on time, volatility, and how close the stock is to the strike. But the sweet spot is right at the strike.

Example:

ABC is trading at 100. You:

- Sell 1 ABC 100 call expiring in 7 days for $1.00

- Buy 1 ABC 100 call expiring in 30 days for $2.50

- Net debit: $1.50

If ABC finishes at 100 after 7 days:

- The short call expires worthless

- The long call might still be worth $2.20

- Your profit is $0.70 or $70 per spread

The payoff profile for a long calendar is similar to a short straddle in that it profits when the underlying stays near the strike price.

Breakeven Zone

Breakeven on a calendar spread isn’t fixed, but you can estimate it. It’s the stock price at short expiration where the value of the spread equals the debit you paid to enter the trade.

There’s no exact formula, but breakeven usually falls just above or below the strike depending on time and implied volatility.

- You make money if the stock stays near the strike.

- You lose money if it moves too far away in either direction.

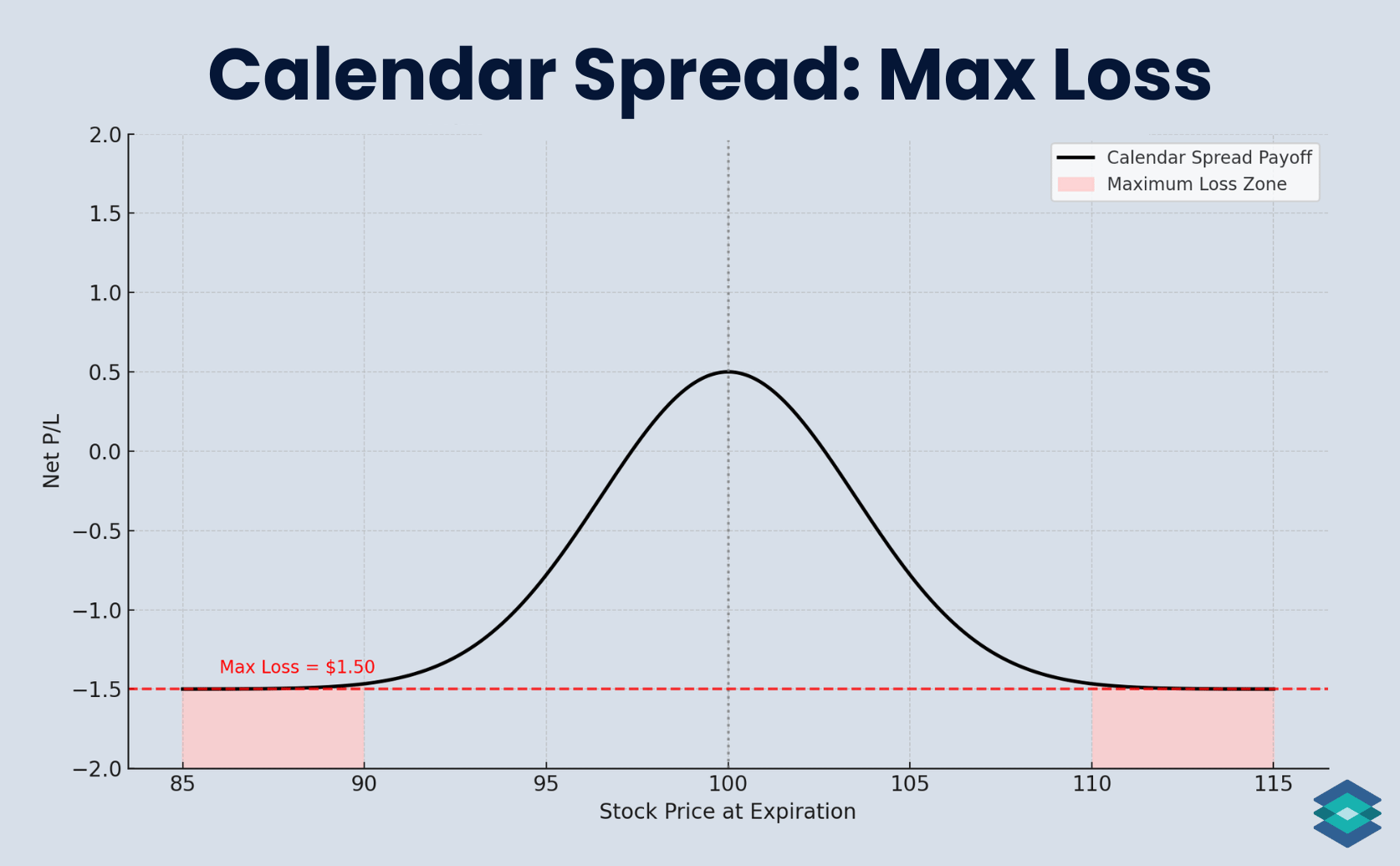

Maximum Loss Zone

Max loss is limited to the net debit paid. In our previous example, that would be $1.50 or $150 per spread since this is what we paid. Max loss happens when the stock moves far enough away from the strike that both options lose value.

Example:

If ABC (100 at entry) moves to 90 or 110 at short expiration:

- The short call expires worthless

- The long call is also worthless

Worst case, the spread is worth zero, and you lose the full $1.50.

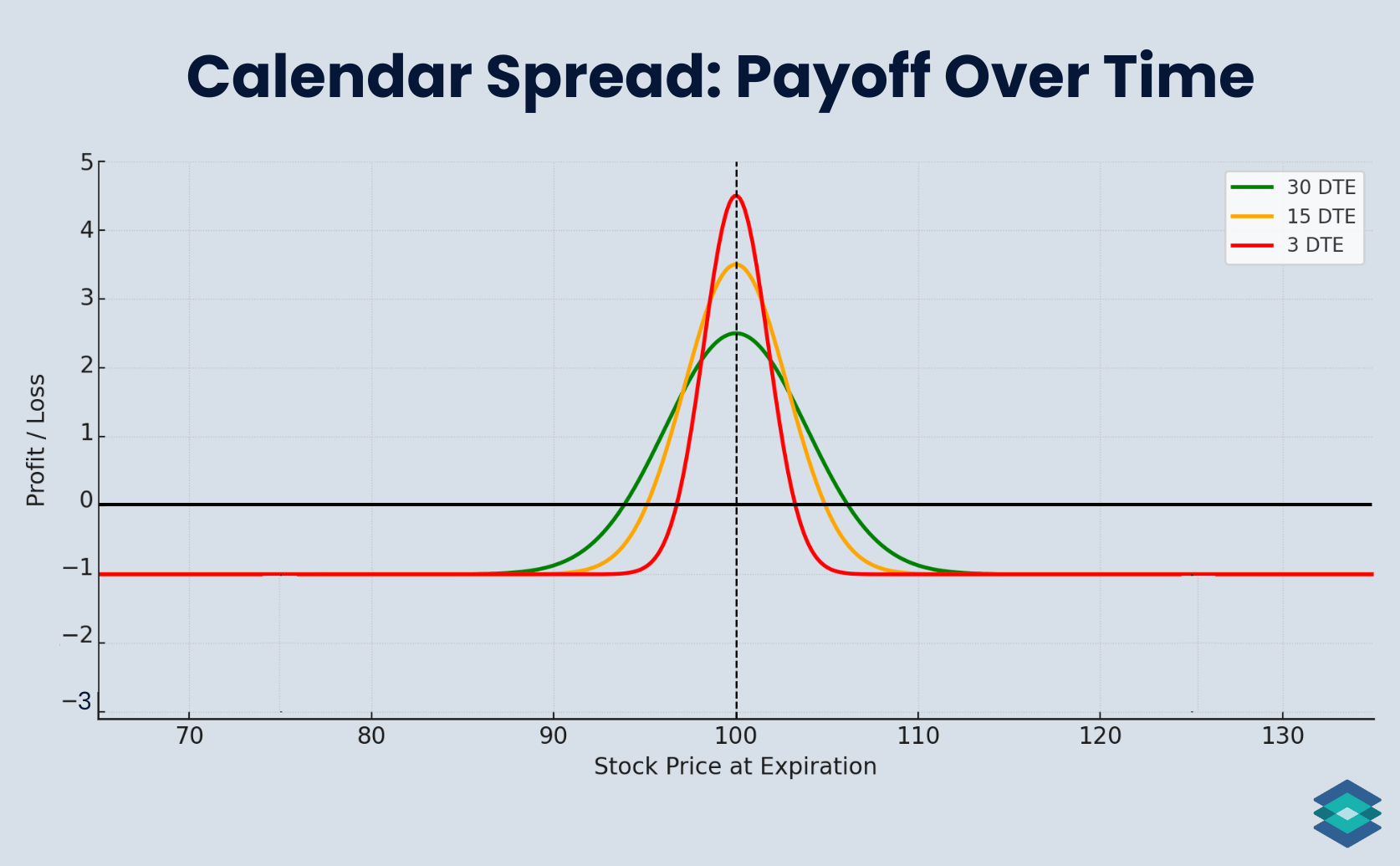

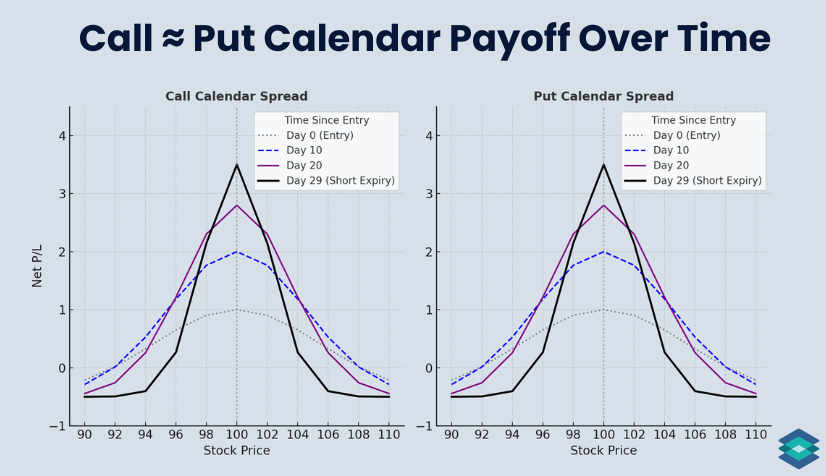

Calendar Spread Payoff Over Time

Over time, assuming the price of the underlying asset and implied volatility remain constant, a long calendar spread should become more profitable as expiration approaches.

The payoff grows sharper and taller as expiration approaches, reflecting the rapid decay of the short option while the long retains value. We can see this illustrated below:

We can see how the sweet spot tightens over time, but profit increases as the short leg decays. This is why many traders look to close calendars just before expiration, when theta is peaking and risk/reward is most favorable.

Call Calendar Spread: Real World Example

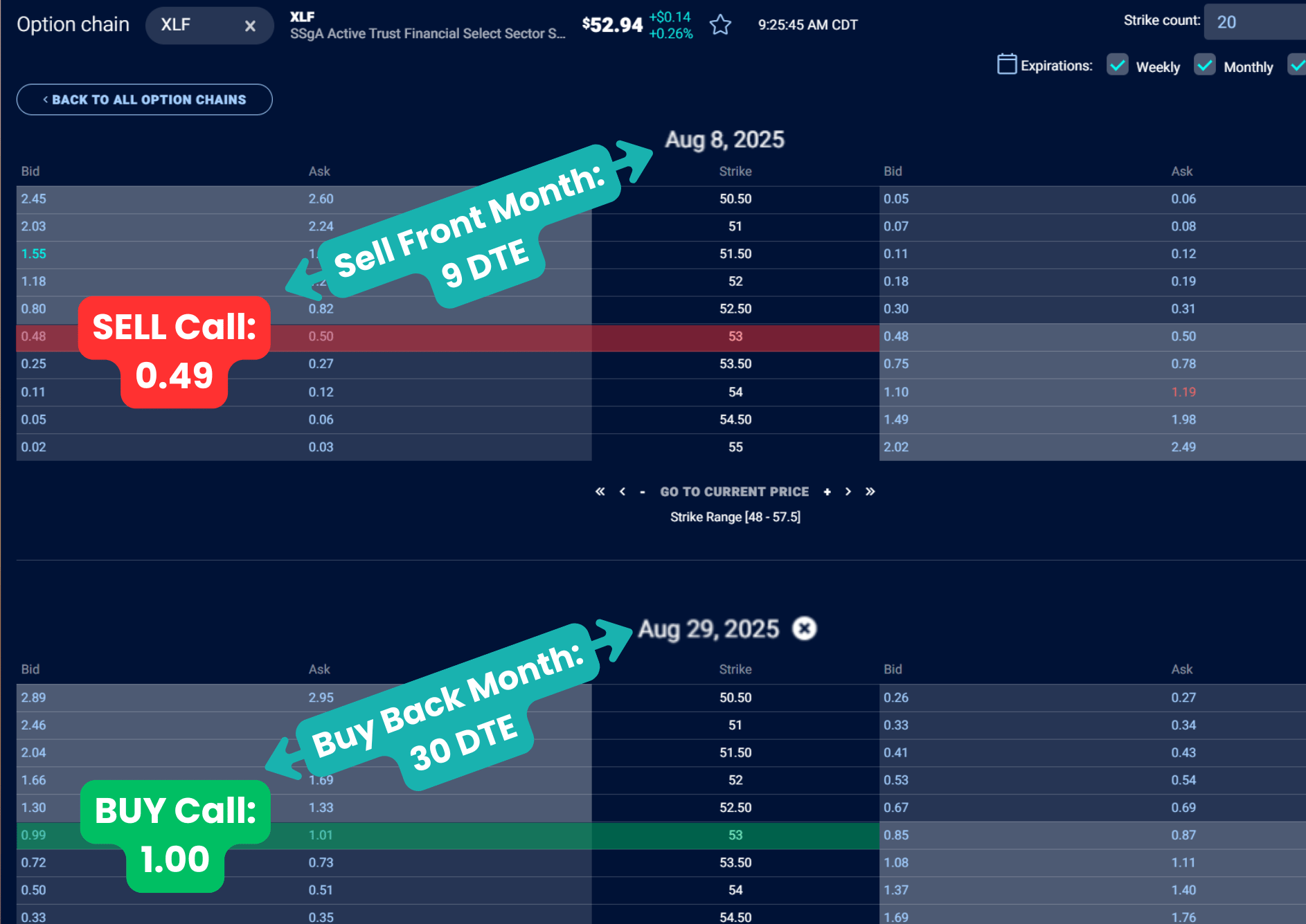

In this example, we’re going to sell the August 8th call option on XLF (Financial Select Sector SPDR Fund) and buy the August 29th call. We’re doing a broad financial earnings play here, so our window is a little narrower than most calendar spreads, which typically have more time.

We’re using XLF because many of the stocks that comprise the ETF have earnings coming up next week. That often drives a build-up in implied volatility, especially in the options expiring around their releases. A calendar spread lets us take advantage of this IV without taking a directional stance.

Let’s head over to the TradingBlock dashboard and find a call to buy and sell:

This trade involves selling 1 front-month call option on XLF at the 53 strike (expiring Aug 8) for 0.49, and buying 1 next-month call at the same strike (expiring Aug 29) for 1.00. The strike price is very near to the ETF price, so this is a market-neutral trade.

As always, it’s best to start at the midpoint between the bid and ask. If the order doesn’t fill right away, work it up in small increments until you get filled. Read more about options liquidity here.

Assuming a midpoint fill, the total net debit is 0.51, or $51 per spread, as shown here:

.png)

XLF Calendar Spread Details

And here are the details of the trade just entered:

- Sell 1 Call: Aug 8 (9 DTE), Strike 53 @ 0.49

- Buy 1 Call: Aug 29 (30 DTE), Strike 53 @ 1.00

- Net Debit Paid: 1.00 (long) – 0.49 (short) = 0.51 total cost

- Breakeven: Not fixed — depends on where implied volatility and price settle

- Max Loss: 0.51 debit = $51 total risk

- Max Profit: Max gain if XLF closes right at 53 on Aug 8

- Profit Zone: Profits if XLF hovers near the strike at front-month expiration

- Risk/Reward: Risking $51, hoping for IV rise or time decay.

Let’s now explore a few trade outcomes!

XLF Calendar: Winning Trade Outcome

XLF ran up ahead of earnings. But when results came in as expected, the ETF slid to 52.90, $0.10 below our optimal zone.

- XLF Price: $52.94 → $52.90 ⬇️

- Expiration: 9 days → 0

- Sell 53 Call (Aug 8): $0.49 → expired worthless

- Buy 53 Call (Aug 29): $1.00 → now worth $0.80

- Net Debit: $0.51 (1.00 – 0.49)

- Net Gain: 0.80 – 0.51 = $0.29 per spread ($29 total)

- All-In Result: Stock finished just under the strike -short call expired worthless, long call held value. Almost as good as it gets for a calendar.

XLF Winner: Under The Hood

IV collapsed post-earnings, but with XLF finishing just under the strike, the short call expired worthless while the long held up. We didn’t pin the strike perfectly, but close enough to make our trade a nice winner. The remaining extrinsic value in the long gave us a clean win of $30 - the Aug 29 call was still worth $0.81, and we originally paid a $0.51 net debit.

XLF Calendar: Losing Trade Outcome

In this trade outcome, financial earnings were horrendous and the stock plummeted 5%. Here’s where things stood on the day the short call expired:

- XLF Price: $52.94 → $50.00 ⬇️

- Expiration: 9 days → 0

- Sell 53 Call (Aug 8): $0.49 → expired worthless

- Buy 53 Call (Aug 29): $1.00 → now worth $0.07

- Net Debit: $0.51

- Net Loss: 0.07 – 0.51 = –$0.44 per spread (–$44 total)

- All-In Result: The stock sold off hard and stayed well below the strike. With both legs out-of-the-money, the short call expired worthless, but the long call collapsed in value, resulting in a loss near the max.

XLF Losing Trade: Under The Hood

The spread picked up some value as XLF moved closer to the 53 strike, the ideal spot for a calendar. But after earnings, the stock dropped hard and stayed below 51. Once the price moves too far from the strike, the difference between the long and short call values begins to contract rather than expand, which ultimately erodes the value of the spread.

The short call expired worthless, and the long call finished at just $0.07, which was almost a max loss.

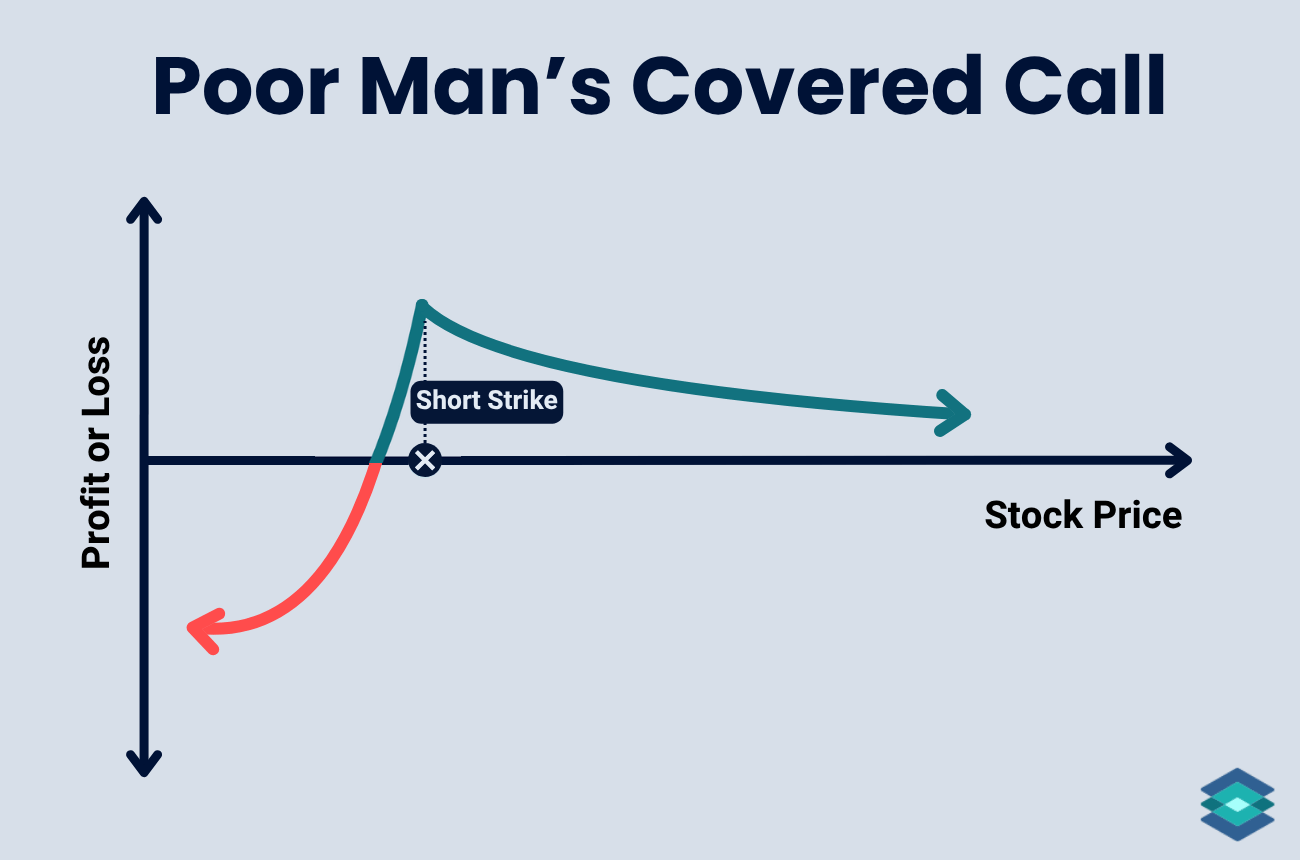

Calendar Spread: Neutral, Bullish & Bearish

In our previous example, we bought an at the money calendar spread, which means the strike price equaled the price of the underlying asset. But if you have a bullish or bearish market tint, you can build your calendar around this by choosing a strike price closer to or further away from the market price:

Just know that placing the strike away from the current price gives the trade a directional bias, while also lowering the odds of landing in the ideal zone. You're aiming for a larger potential gain if your directional view is correct, but the probability of success decreases.

Choosing Calls vs. Puts

As we mentioned earlier, it’s not the type of option, but the strike price that determines whether a calendar spread has a bullish or bearish bias.

That said, there are reasons advanced traders often lean one way:

- Calls tend to have lower to moderate implied volatility in bullish markets, making the long leg cheaper.

- Puts usually carry higher IV in bearish markets, which helps you collect more on the short leg.

Calendar Spread: Risk Management

As we learned, you won't know your exact max profit or breakevens on a calendar spread at trade initiation. But there are several methods for managing your position and determining how it's performing.

Let’s start with perhaps the most important: delta.

1. Delta: Neutral calendar spreads start near delta-neutral but can quickly gain directional exposure. If the stock drifts from your strike, your net delta can shift. For example, a rally might leave you with unexpected bullish exposure just a few days in.

2. Time Decay Monitoring: Watch how fast your short option is losing value compared to your long option. The short option should decay faster, especially as it approaches expiration. If this isn't happening, your trade may be in trouble.

To monitor this, watch your position’s net theta. Theta is the option Greek that tells us how much value an option is expected to shed every day (in a constant environment). A positive theta means time decay is working in your favor. If theta turns flat or negative, that’s a red flag.

3. Implied Volatility Changes: Since this is a net debit trade, rising volatility helps calendar spreads (benefits the long option more), while falling volatility hurts them. Monitor the volatility environment and consider closing if volatility drops significantly.

4. Time-Based Exit Rules Most traders close calendar spreads with 5-10 days until short expiration (assuming it's not an event play like earnings). Don't hold through the final week unless you're confident the stock will stay near your strike.

5. Assignment Risk: If you're trading American-style options (like most stocks and ETFs), your short option is exposed to early assignment risk, especially near expiration if it's in the money. To avoid this, consider using European-style index options like SPX or NDX, which can’t be exercised early.

Calendar Spreads and The Greeks

⚠️ Calendar spreads are powerful tools for managing time decay and volatility, but they require a solid understanding of how options work. This strategy isn’t right for everyone. Commissions and slippage can all impact results, which are not reflected in the examples above. Before trading options, read The Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options.

FAQ

A calendar spread is an options strategy that involves selling a near-term option and buying a longer-dated option, both at the same strike. The trade benefits from time decay as the short option approaches expiration, while the long option ideally retains value.

You set it up a calendar spread by selling an option with a closer expiration and buying the same type of option (call or put) with a later expiration, using the same strike price. The trade is entered for a net debit.

Let’s say ABC is trading at $100. You sell a 7-day 100 call for $1.00 and buy a 30-day 100 call for $2.50, paying $1.50 total.

The best time to trade a calendar is when implied volatility is low and you expect the stock to stay near the strike price in the short term. Rising volatility after entry can also help increase the spread’s value.

Calendar spreads have a lower probability of large profits but a wide zone of breakeven. Success depends on how tightly the stock trades around the strike.

Calendar spreads lose when the underlying stock moves too far from the strike, causing both options to lose value. A sharp move in either direction reduces the spread’s worth.

A calendar spread uses the same strike but different expirations. A vertical spread uses the same expiration but different strikes, making it more directional.

.avif)